Object of the Week: Burgess’s Film Collection

-

Graham Foster

- 27th October 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

-

tagged as

- Archive

- Burgess 100

- Collections

- Film

- Gibraltar

- Object of the Week

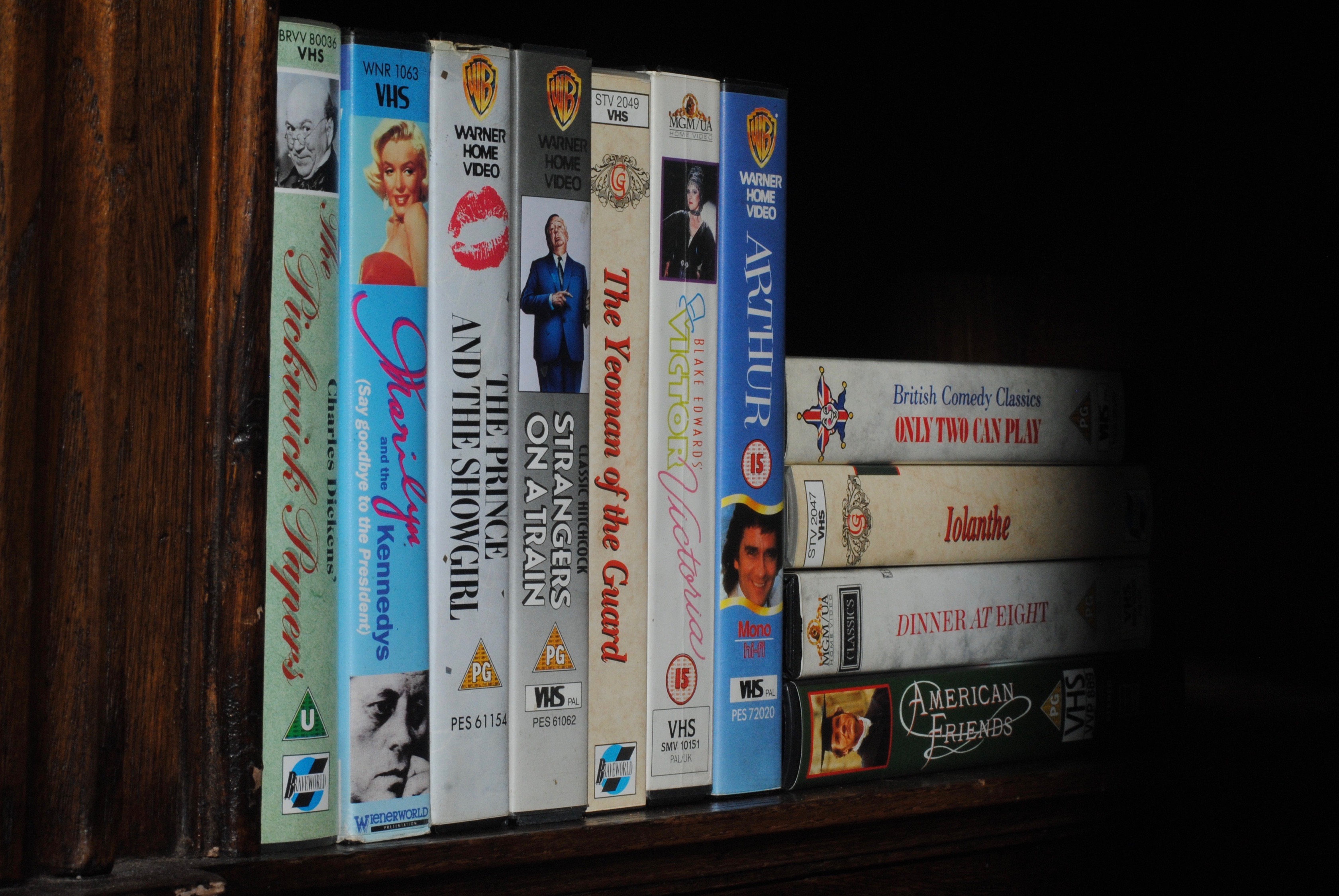

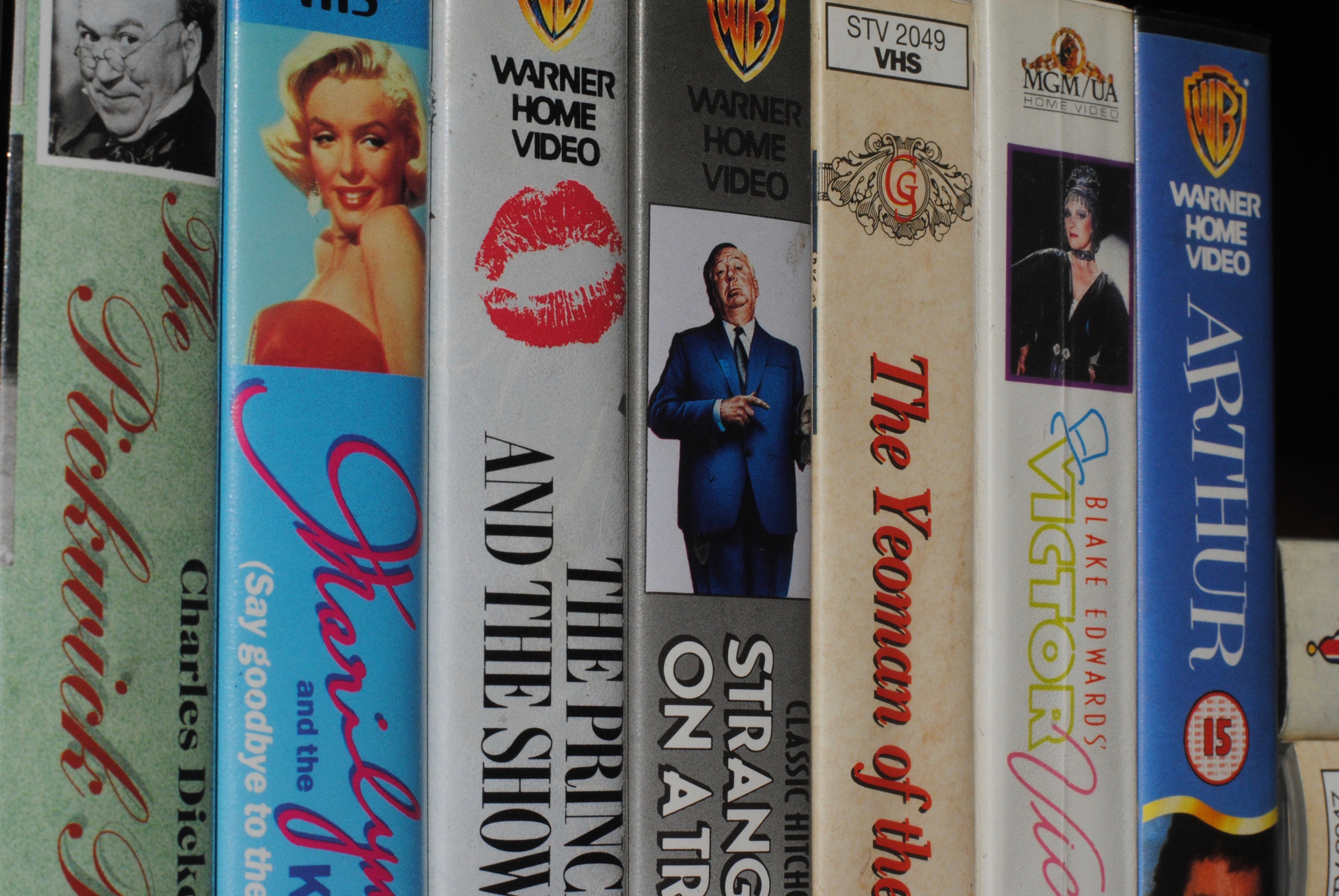

VHS cassettes became popular in the last decade of Anthony Burgess’s life, and the small collection of films on video cassettes in the Burgess Foundation archive shows that he embraced the new technology and watched many films from the comfort of his own living room.

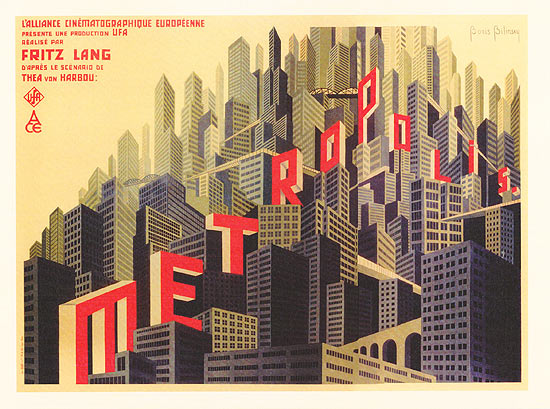

Burgess was an avid film viewer throughout his life, first becoming aware of cinema during his childhood in Manchester. During the 1920s and 1930s, his father, Joseph Wilson, played piano for the silent cinemas of the city, and Burgess remembers seeing Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in 1927: ‘Seeing it at the age of ten remains one of the major artistic experiences of my life; I still list Metropolis among the best dozen films ever made.’

After Burgess was drafted into the army in 1940, he was stationed in Gibraltar, where he reviewed films for the Gibraltar Chronicle. These were mostly war-set romances or adventures, but he proved to be a tough critic to please. Of the film Till We Meet Again, a 1944 film about an American airman who is sheltered in a French nunnery, Burgess writes: ‘Hollywood always has a clumsy touch when dealing with religion and the religious. There is a rather unpleasant piquancy in the way the young nun is made to pose as the wife of the airman’, though he begrudgingly concludes that the film is ‘a reasonable half-night’s entertainment.’

There are also reviews of the 1944 films You Can’t Ration Love (‘an awful waste of dollars’), National Barn Dance (‘flimsy, unpretentious fare’), Pin-up Girl (‘how insulting the whole thing is, how lacking in grace, in intelligence, in charm!’), Adventures of a Rookie (‘I will not take the trouble to say anything good, either from an aesthetic or an economical point of view’). In his final review, he confesses that during his months of reviewing, he ‘had so little opportunity to praise’, and that for his final film, ‘it would have spoilt the whole pattern of my critical career if the Theatre Royal had suddenly and surprisingly put on a masterpiece’.

Burgess continued writing about films after he had been published as a novelist, and his experiences of watching, reviewing and writing films can be seen in most of his fiction. In his first published novel, Time for a Tiger (1956), the characters frequent the Film Society in Colonial Malaya, while in his final novel, Byrne (1993), the eponymous protagonist writes music for film. More overtly, The Pianoplayers (1986) tells a fictionalised story of his youth in the silent cinemas of Manchester, and Kenneth Toomey works in Hollywood and attends a film festival in Nazi Germany in Earthly Powers (1980).

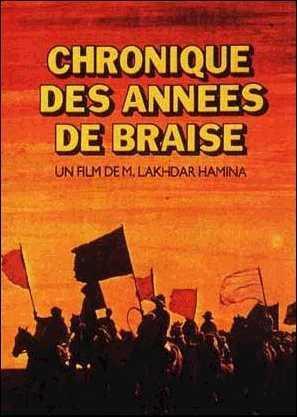

Burgess’s career as a film critic continued to develop, and in 1975, he was invited to join the judging panel of the Cannes Film Festival, alongside director George Roy Hill and actress Jeanne Moreau among others. They judged films such as Martin Scorsese’s Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, Bob Fosse’s Lenny, and Werner Herzog’s The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser before awarding the Palme d’Or to the Algerian film Chronicle of the Years of Fire. Burgess described this experience as a ‘descent into madness’, and remembers being ‘assaulted by Tommy’, Ken Russell’s rock opera starring The Who.

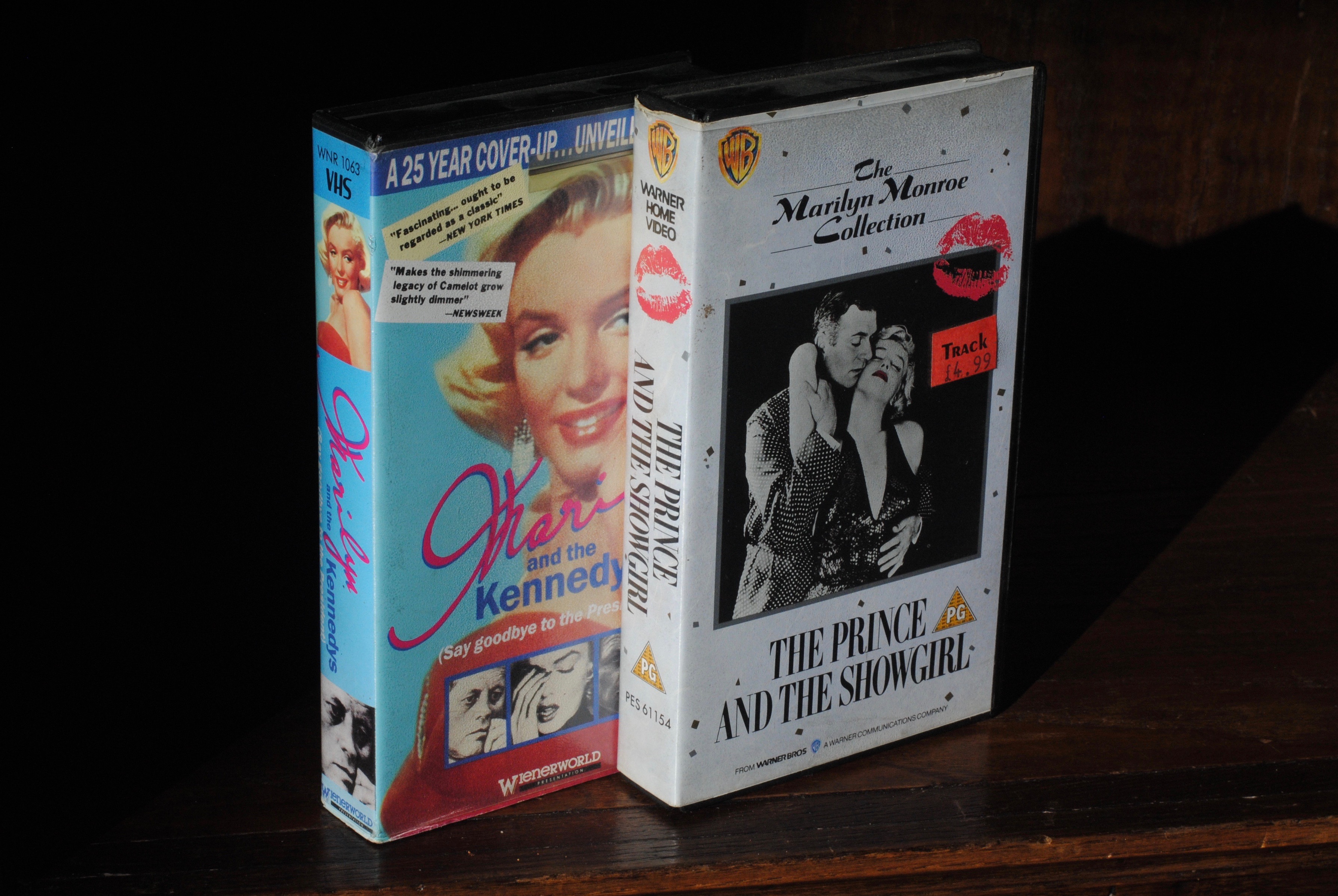

Burgess’s private collection of VHS gives some understanding of the films he watched for enjoyment, not for the business of critique or judging. There are video cassettes of films such as Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951), Blake Edwards’s Victor Victoria (1982), Tony Richardson’s Tom Jones (1963), George Cukor’s Dinner at Eight (1933), and a rather incongruous copy of Arthur (1981) starring Dudley Moore.

Other films in the collection have connections to Burgess’s work. The Prince and the Showgirl (1957) stars both Marylin Monroe and Laurence Olivier. In 1989, Burgess wrote an obituary for Laurence Olivier, praising the actor. He writes: ‘Olivier belongs to an important past, and we must regret that so little of it can be preserved. The films are something, but they are not enough. Olivier was much more than his films.’ What Burgess means here is that Olivier connected the worlds of film and theatre, and brought theatrical techniques to his on-camera acting. Perhaps Burgess saw a kindred spirit, as his own writing blended the literary and the cinematic, both in his novels and his own screenplays.

The film collection also contains the documentary Say Goodbye to the President: Marilyn and the Kennedys (1985). Burgess was seduced by Monroe’s iconic status: ‘That she was a great comic ought to detract from her divine glamour. She had a quality she may have learnt from Mae West, the blonde seductress who mocked seduction, indeed mocked sex: this was the intimation that she, the true she, was somewhere outside her body, that her body was a kind of glorious impersonation, an image of an archetypal love goddess.’ Burgess never met Monroe, but his French translator, Georges Belmont, conducted a long interview with her in 1960, which was later published as the book Marylin Monroe and the Camera (2000).

Reflecting on the importance of film in 1990, Burgess wrote: ‘if the task of literature is to stud the brain with quotations, cinema’s job is to cram it with images which transcend story-line and feed the need for myth.’ By this point, Burgess had worked in the film industry, producing screenplays such as The Bawdy Bard (a musical based on the life of Shakespeare), The Spy Who Loved Me (an unproduced version of the James Bond film) and the caveman dialogue for Quest for Fire. He also worked on film adaptations of his own novels, including A Clockwork Orange, The Doctor is Sick, Enderby, and The Wanting Seed. None of these adaptations were ever filmed, yet these scripts are evidence of a writer who worked in both quotation and image, and was part of a generation for whom cinema was a vital part of the cultural environment.