Object of the Week: Burgess’s Library of Inscribed Books

-

Graham Foster

- 18th October 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

Throughout his career, Burgess enjoyed close relationships with other writers. Even before his first book had been published, he would associate with literary figures. In the early 1940s, while on leave from his Second World War posting to Gibraltar, he frequented the pubs of ‘Fitzrovia’, the area around Fitzroy Square in London. Pubs such as the Wheatsheaf and the Fitzroy Tavern were the favoured haunts of writers like George Orwell and Dylan Thomas, among other poets and novelists. These pubs survive today, and the walls of the Wheatsheaf bear commemorations to Thomas, Orwell and Burgess.

After Burgess had published his first novel in 1956, he started to meet other, more established writers. Kingsley Amis had been in Burgess’s consciousness since the publication of Lucky Jim in 1954, but they didn’t meet until the mid-1960s. Amis remembers his initial acquaintance with Burgess: ‘Attempts were made to set up a friendship. I was attracted by John’s air of independence, of being completely his own man, above the literary or any other arena […] and the gleams of humour that lit up his air of slight solemnity’.

In 1962, before he had met Burgess, Kingsley Amis reviewed A Clockwork Orange. He said: ‘Mr Burgess has written a fine farrago of outrageousness, one which incidentally suggests a view of juvenile violence I can’t remember having met before’. Burgess went on to review many of Amis’s novels, beginning with I Want it Now in 1968, and he selected Lucky Jim and The Anti-Death League (1966) for Ninety-Nine Novels, his book about the best fiction published after 1939.

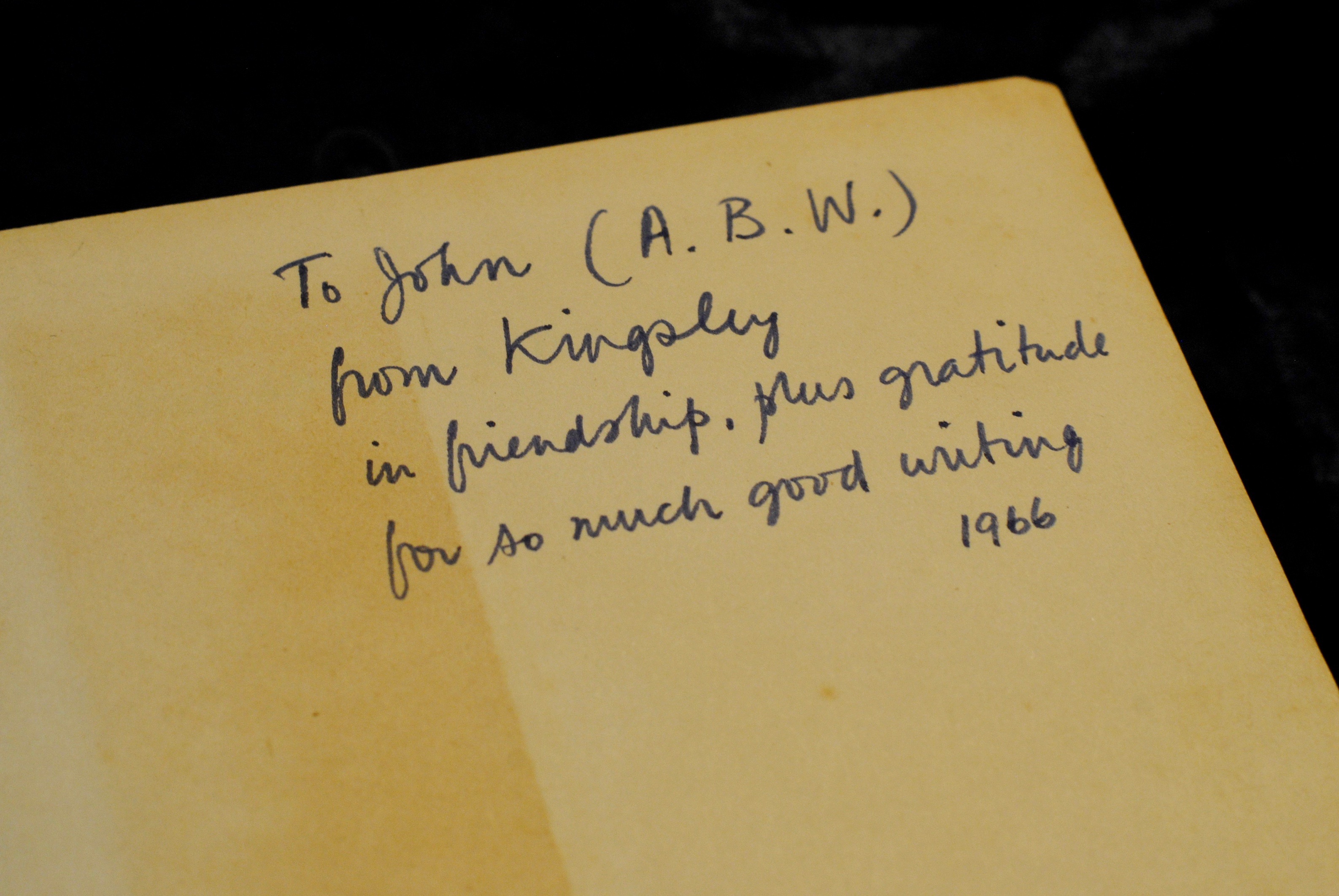

Amis inscribed a copy of The Anti-Death League as a gift for Burgess. The inscription reads: ‘To John (A.B.W.) from Kingsley in friendship, plus gratitude for so much good writing. 1966’. In return Burgess inscribed a copy of Tremor of Intent (1966) for Amis, though Amis sent no letter of thanks, which resulted in ‘the severance in what we had had in the way of a friendship’.

Amis claimed that he stopped reading Burgess’s novels following the publication of Tremor of Intent because of ‘too much wordage, wordplay, wordiness and not enough character, story etc.’ Amis made exceptions to this rule in 1978 by reviewing Burgess’s 1985, and in 1987 he reviewed Little Wilson and Big God. According to Amis, Burgess responded to the review in person when they met at the Olympia Book Fair of that year: ‘I was sorry you couldn’t find something a little kinder to say about my autobiography when you reviewed it. After all I have been extremely kind about your novels in the past’.

Burgess met the novelist Olivia Manning in the early-1960s, and became friends with her and her husband, the BBC radio producer Reggie Smith. There is a long correspondence between Burgess and Manning in the archives at the Burgess Foundation, which reveals their relationship to be playful, gossipy and competitive. In 1962, Burgess inscribed a copy of The Wanting Seed to Manning, calling her ‘la ottima fabbra’, meaning ‘the better maker’. This inscription, playing on T.S. Eliot’s dedication to Ezra Pound in The Waste Land (1922), indicates Burgess’s high regard for Manning’s fiction.

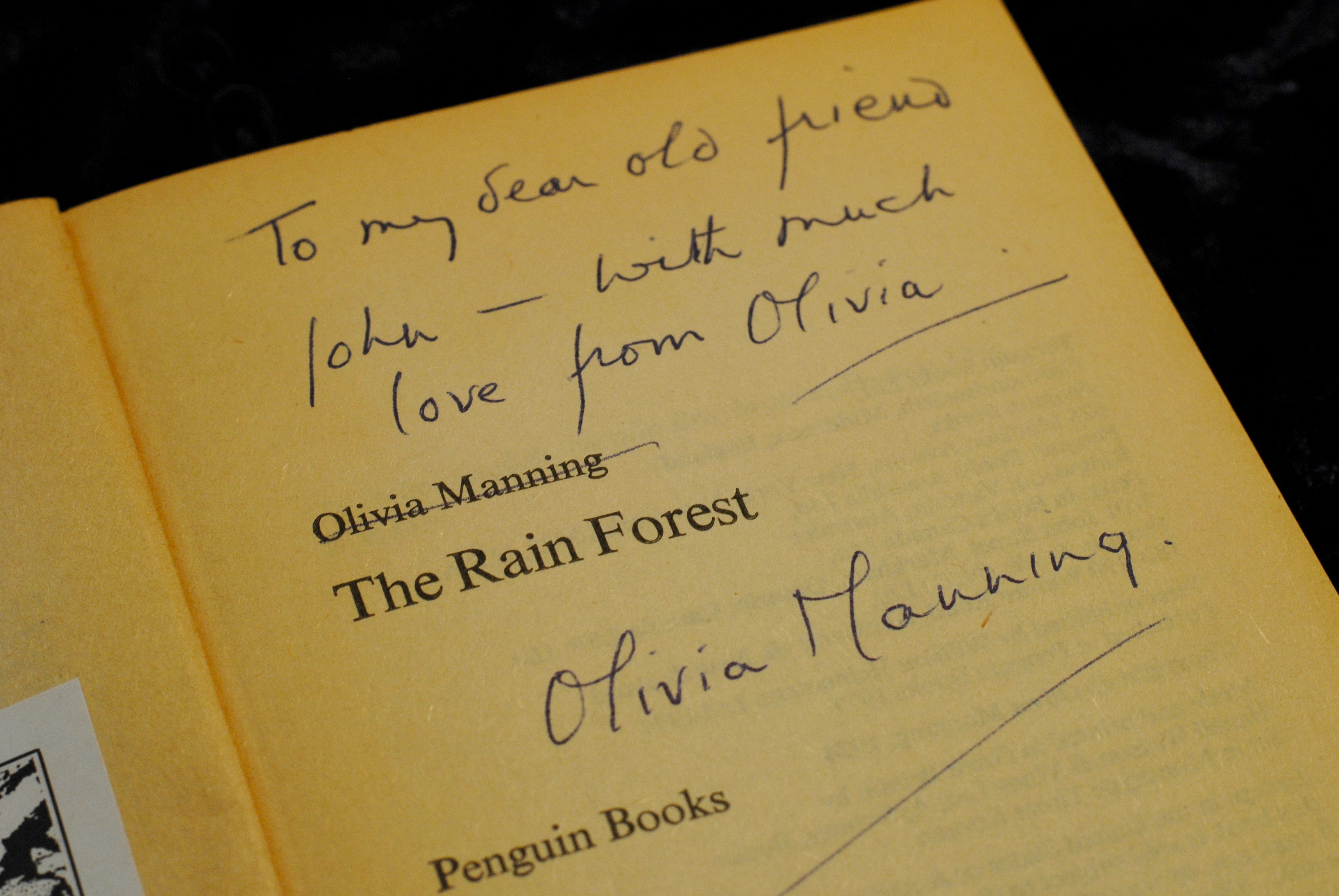

Two copies of Manning’s novels in the Burgess Foundation library bear her inscriptions: The Rain Forest (1974) reads ‘To my dear old friend John – with much love from Olivia’; and The Battle Lost and Won (1978) reads ‘To John – with affectionate, admiring & grateful good wishes, love from Olivia’.

Francis King claims, in his autobiography, that Burgess proposed marriage to Manning after the death of his first wife in 1968. If the anecdote is true, the episode did not sour their friendship, which continued until Manning’s death in 1980, when Burgess wrote her obituary for the Observer.

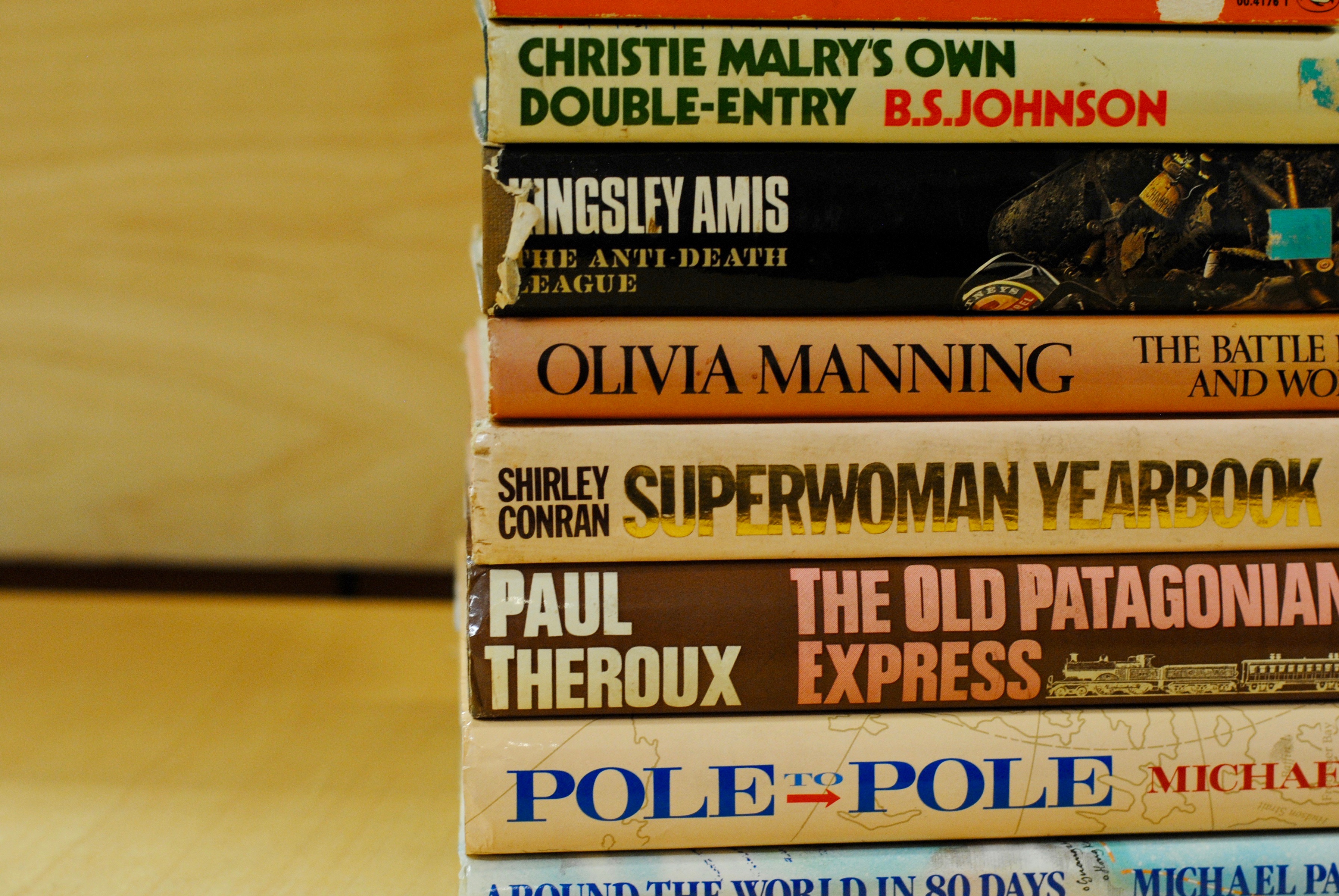

There are numerous other inscriptions in the book collection, including authors such as Paul Theroux, Umberto Eco and B.S. Johnson, who inscribed a copy of his 1973 novel Christy Malry’s Own Double-Entry with ‘To Anthony Burgess with respect and many thanks for his generosity towards this novel and B.S. Johnson’.

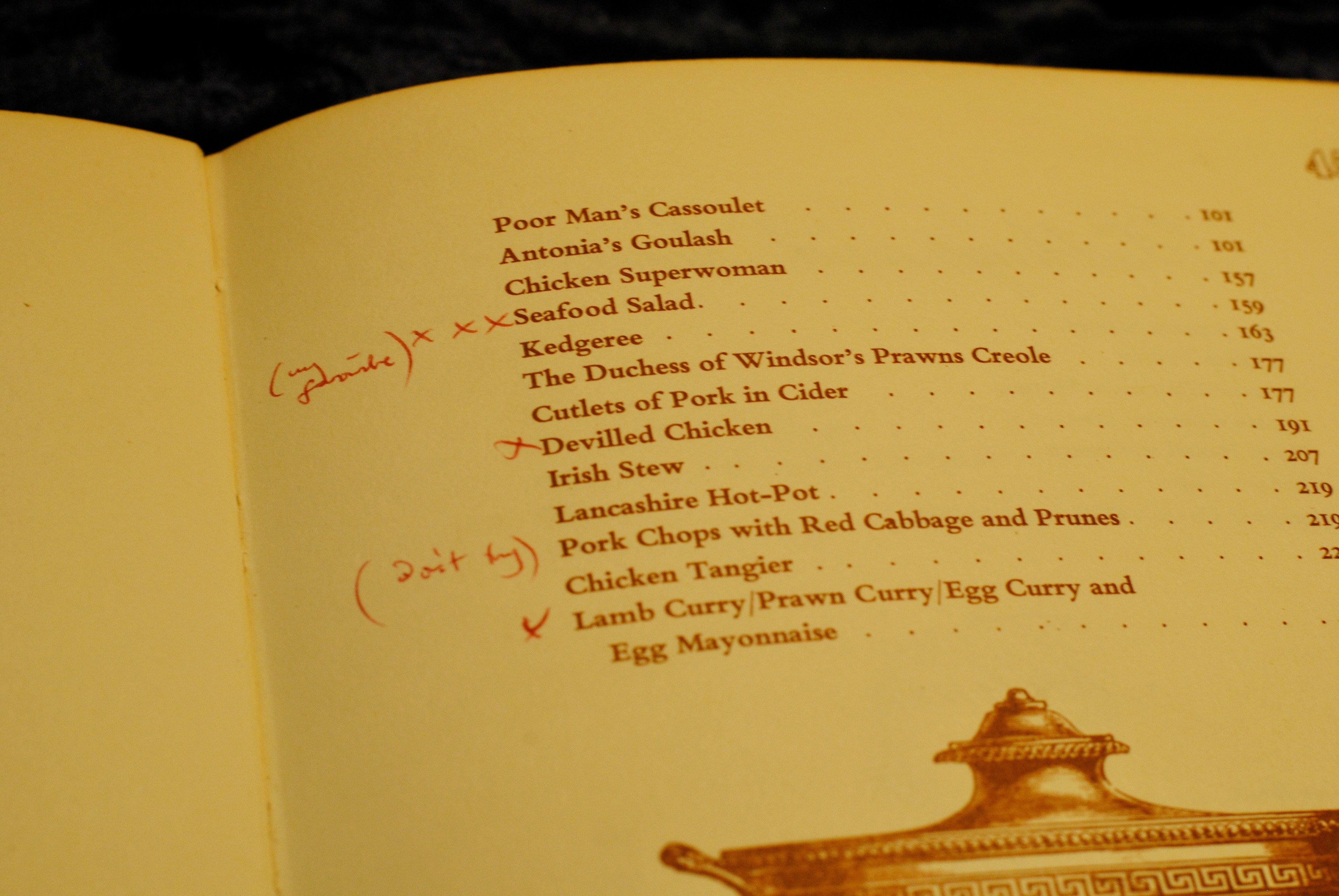

Elsewhere in Burgess’s library there are some unexpected inscriptions. In particular, The Superwoman Yearbook by Shirley Conran (1978) is inscribed ‘(The Happy Cooker) with best wishes to Anthony Burgess from Shirley Conran’. Conran, who was Burgess’s neighbour in Monaco, has also marked certain recipes in the book, such as ‘Nerve Juice’, Chicory and Orange Salad, Ena Sharples’s Lancashire Roughened Potatoes, and Princess Margaret’s Avocado and Pear Soup. Burgess later read and commented on an early draft of Conran’s best-selling novel, Lace, published in 1982.

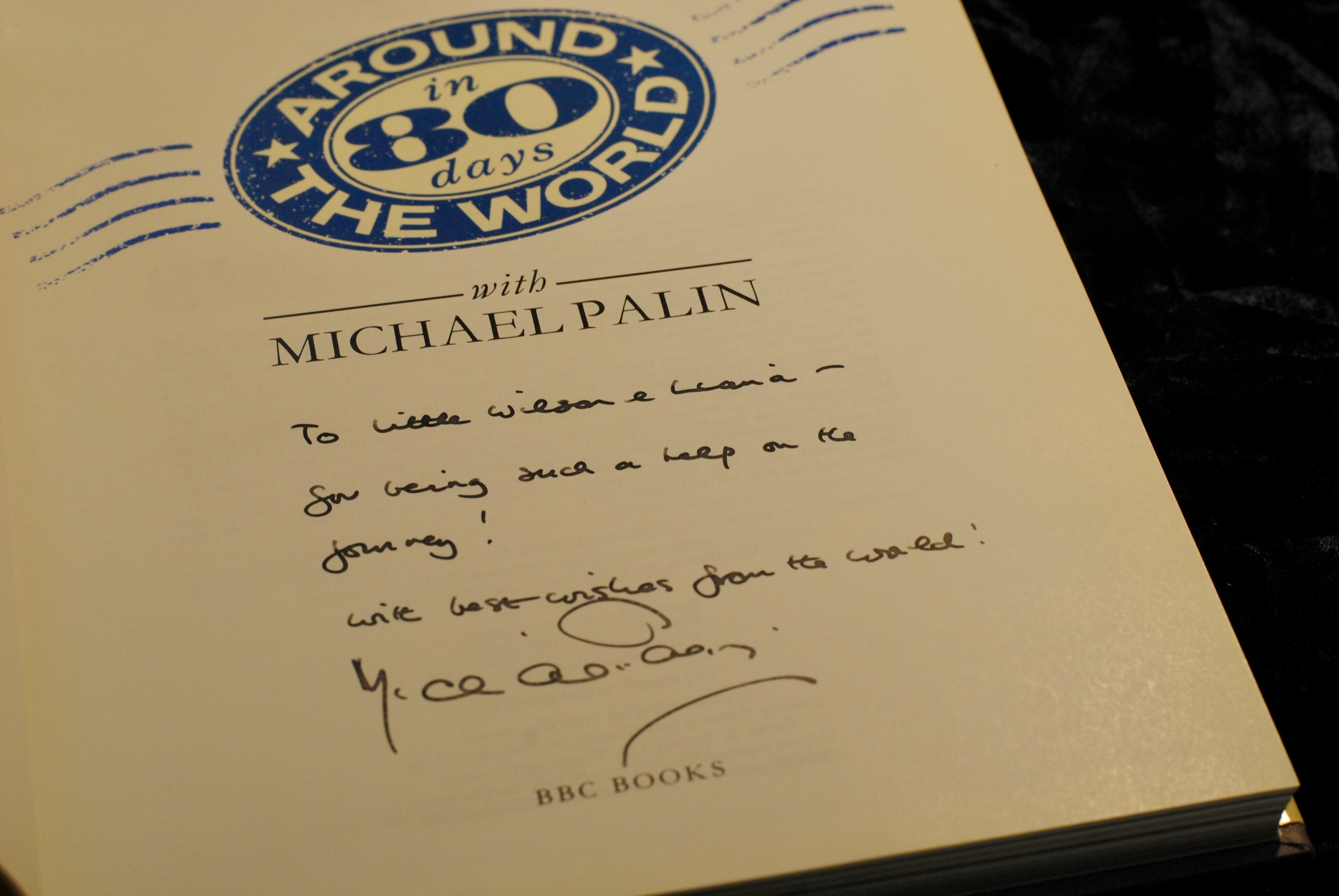

There are also two inscribed books by the comedian Michael Palin. Burgess’s copy of Around the World in 80 Days (1988) reads ‘To Little Wilson and Liana – for being such a help on the journey! With best wishes from the world! Michael Palin’. This refers to Palin’s reading of Burgess’s autobiography while he undertook his trip. Burgess’s copy of Pole to Pole (1992) bears the inscription ‘In celebration of starting the week together’, a reference to their joint appearance on the BBC radio programme Start the Week in October 1992.

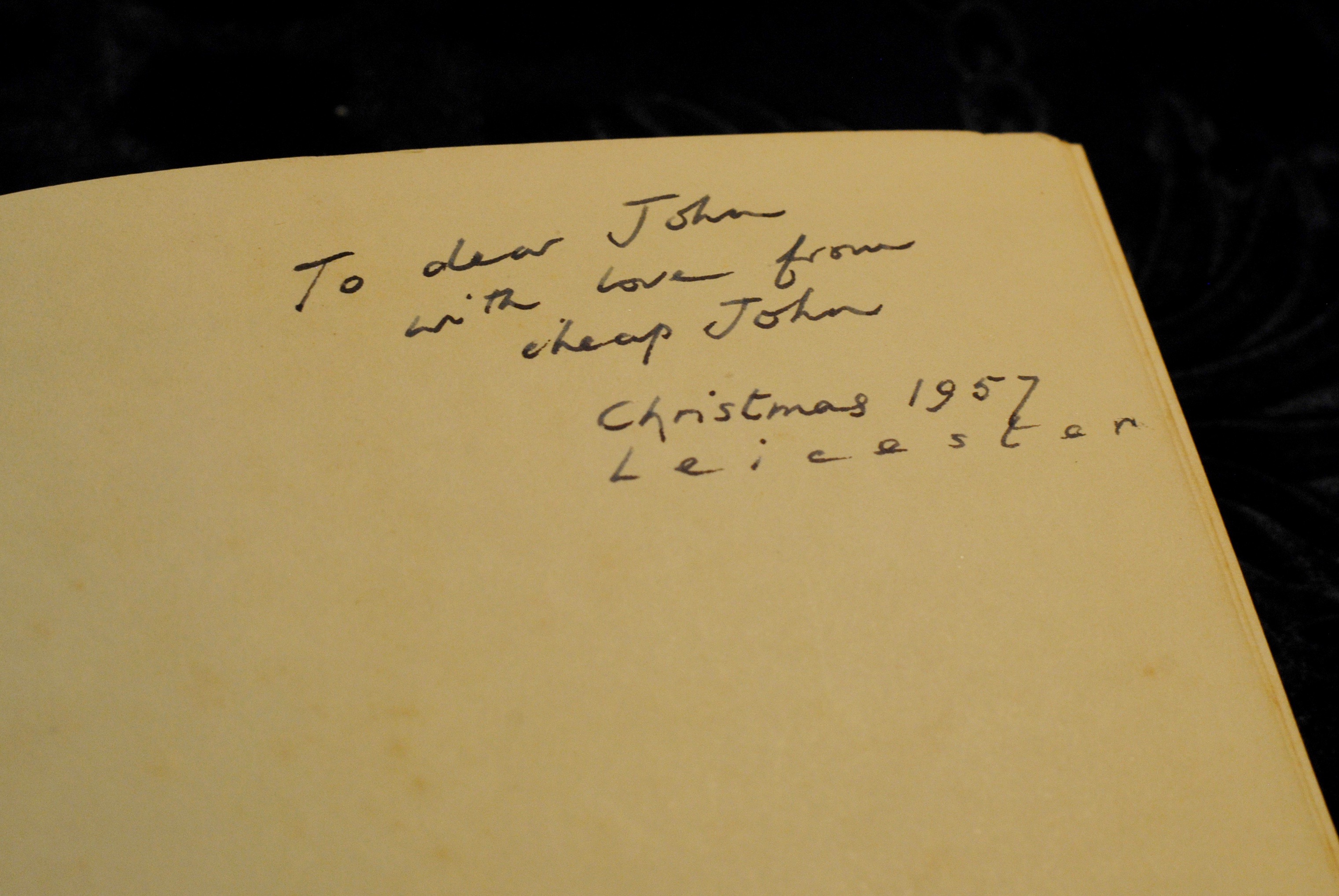

Some inscriptions in Burgess’s library are even more surprising. That Burgess should own a copy of Robert Graves’s autobiography Goodbye to All That (1957) is not unexpected, but the inscription in the book is not from Graves. It reads ‘To dear John with love from cheap John. Christmas 1957, Leicester’ in Burgess’s own handwriting.

Burgess’s own copy of the first edition of One Hand Clapping (published under the pseudonym Joseph Kell in 1961) also has a self-inscription, reading ‘To Joejohn from Johnjoe and to Kell with Burgundy’. These inscriptions show that Burgess didn’t take his multiple literary identities too seriously (a fact that is bolstered by his unfavourable review of his own novel Inside Mr Enderby in the Yorkshire Post in 1963), but they also show a desire to personalise significant books in his collection.