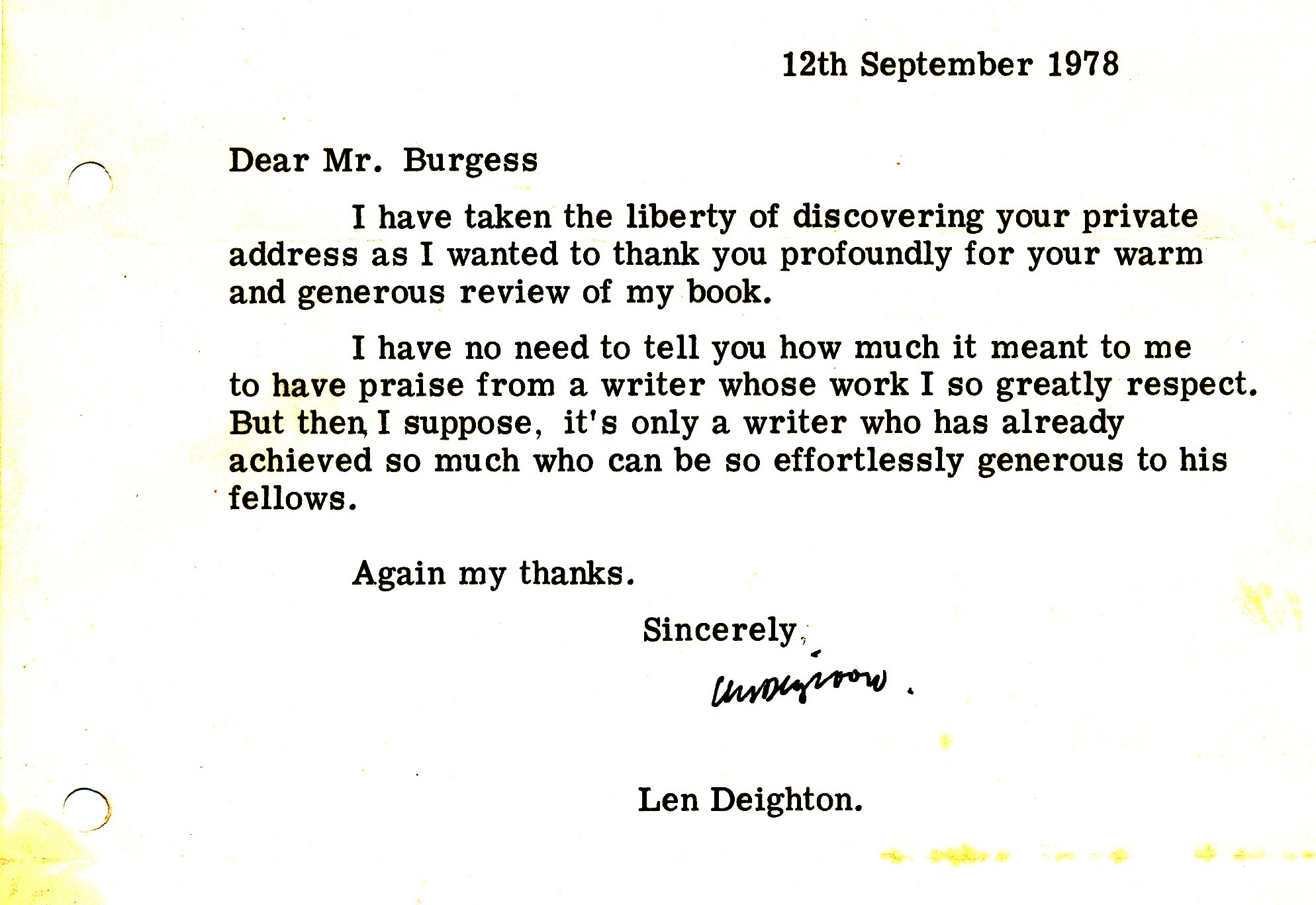

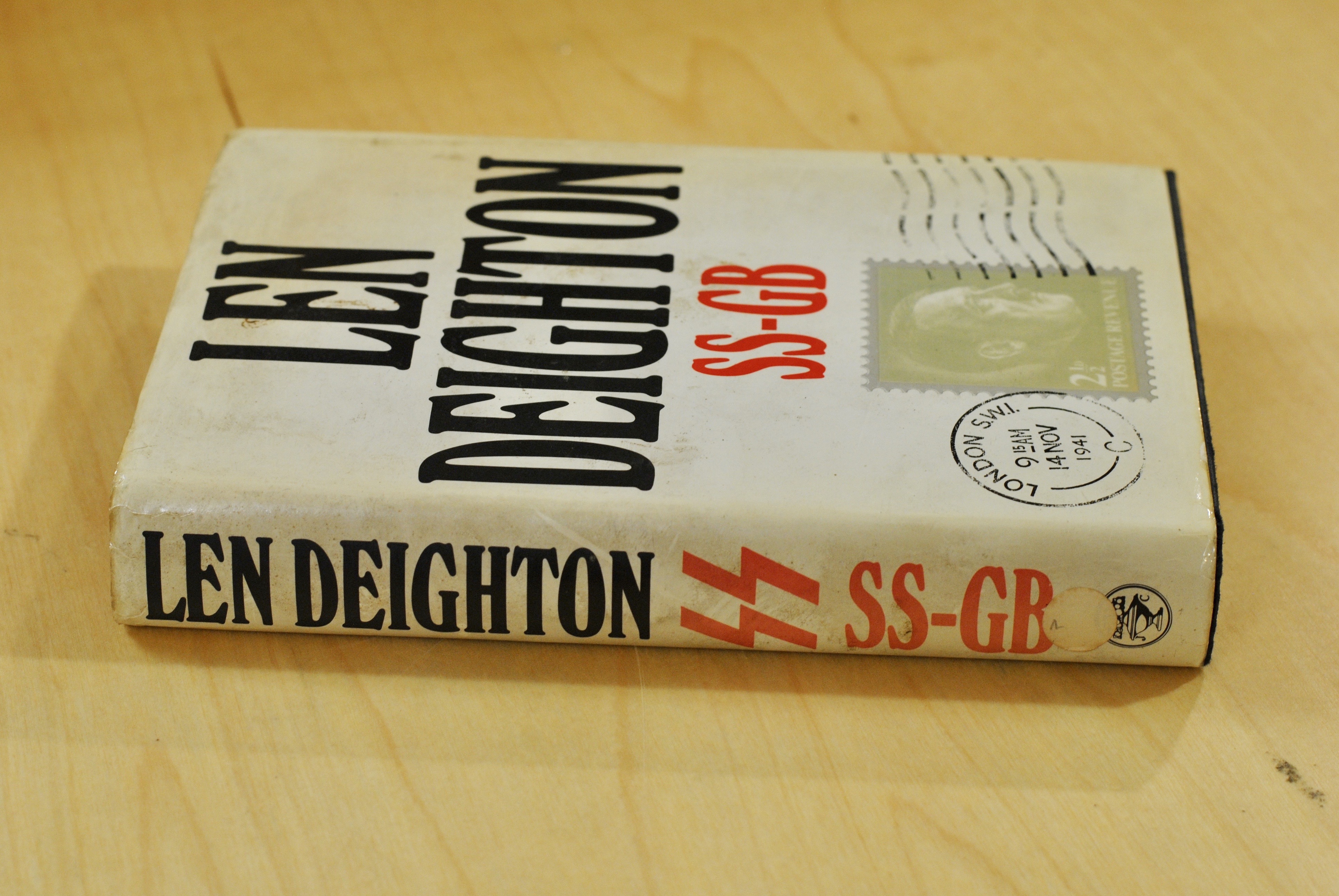

This letter hints at the mutual respect and admiration between Anthony Burgess and Len Deighton. The letter is a response to Burgess’s review of Deighton’s SS-GB in the Observer (27 August 1978), a review that praises the novel as ‘one of Deighton’s best’. Of the author himself, Burgess writes: ‘Apart from his virtues as a storyteller, his passion for researching his backgrounds gives his work a remarkable factual authority’.

When SS-GB was released, Burgess had already been impressed by other novels by Deighton. In particular, Burgess was fond of Bomber (1970) which he added to his Ninety-Nine Novels (1984), and stated that Deighton ‘represents a new and important strain in contemporary fiction and is to be admired for his courage’.

Born in 1929, Deighton began writing professionally in 1962, the same year Burgess published A Clockwork Orange, though his chosen genre was very different from Burgess’s. Primarily writing military thrillers and spy novels, he also wrote a work of speculative fiction and a novel set in the film industry. His first novel, The IPCRESS File was adapted into a film starring Michael Caine in 1965. Deighton was one of the first authors to use a word processor, Bomber being the first novel he completed on his IBM Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter (MT/ST). This machine was delivered to his house in 1968, its delivery facilitated by a crane and the removal of one of Deighton’s windows. Burgess would not experiment with a word processor until 1985.

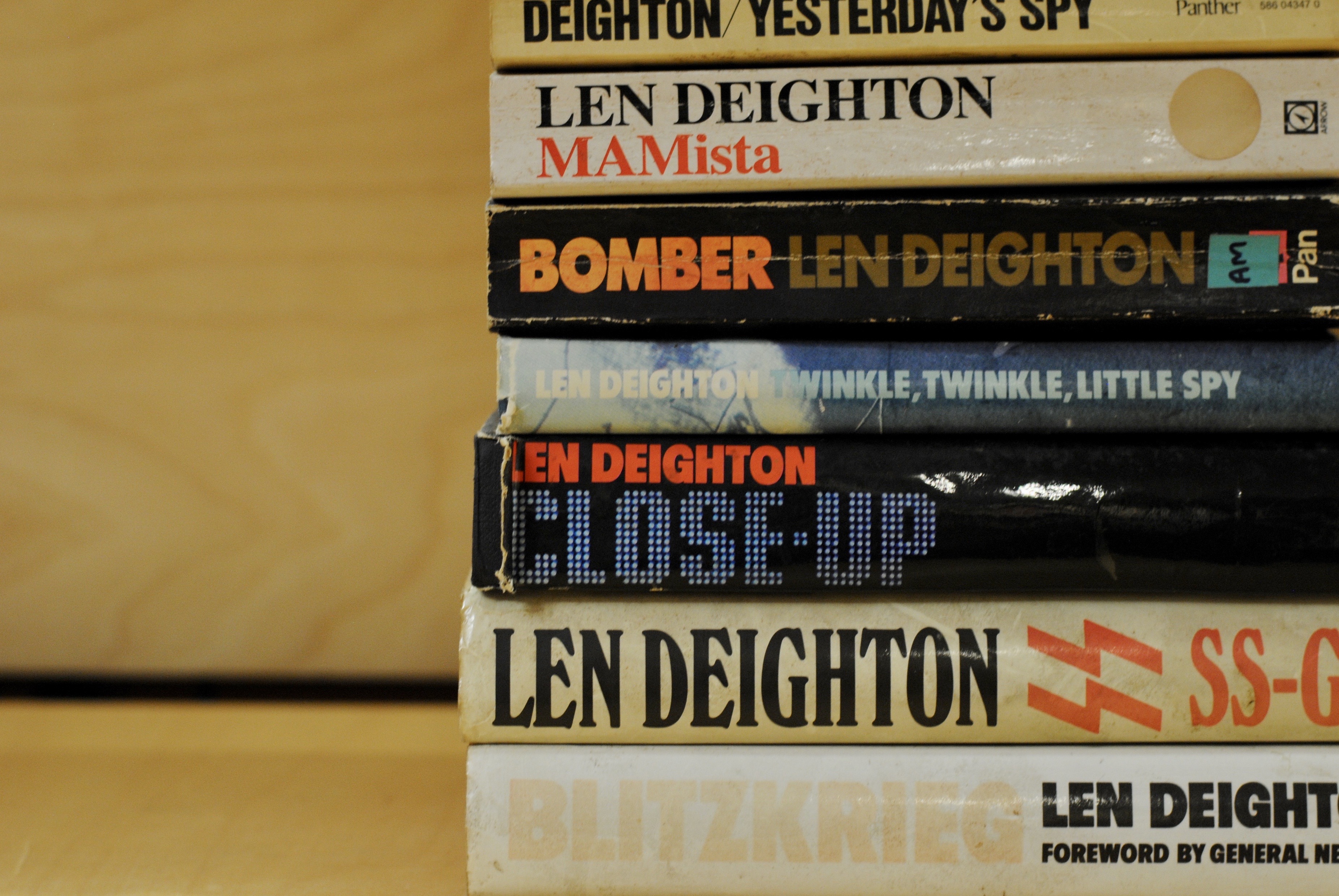

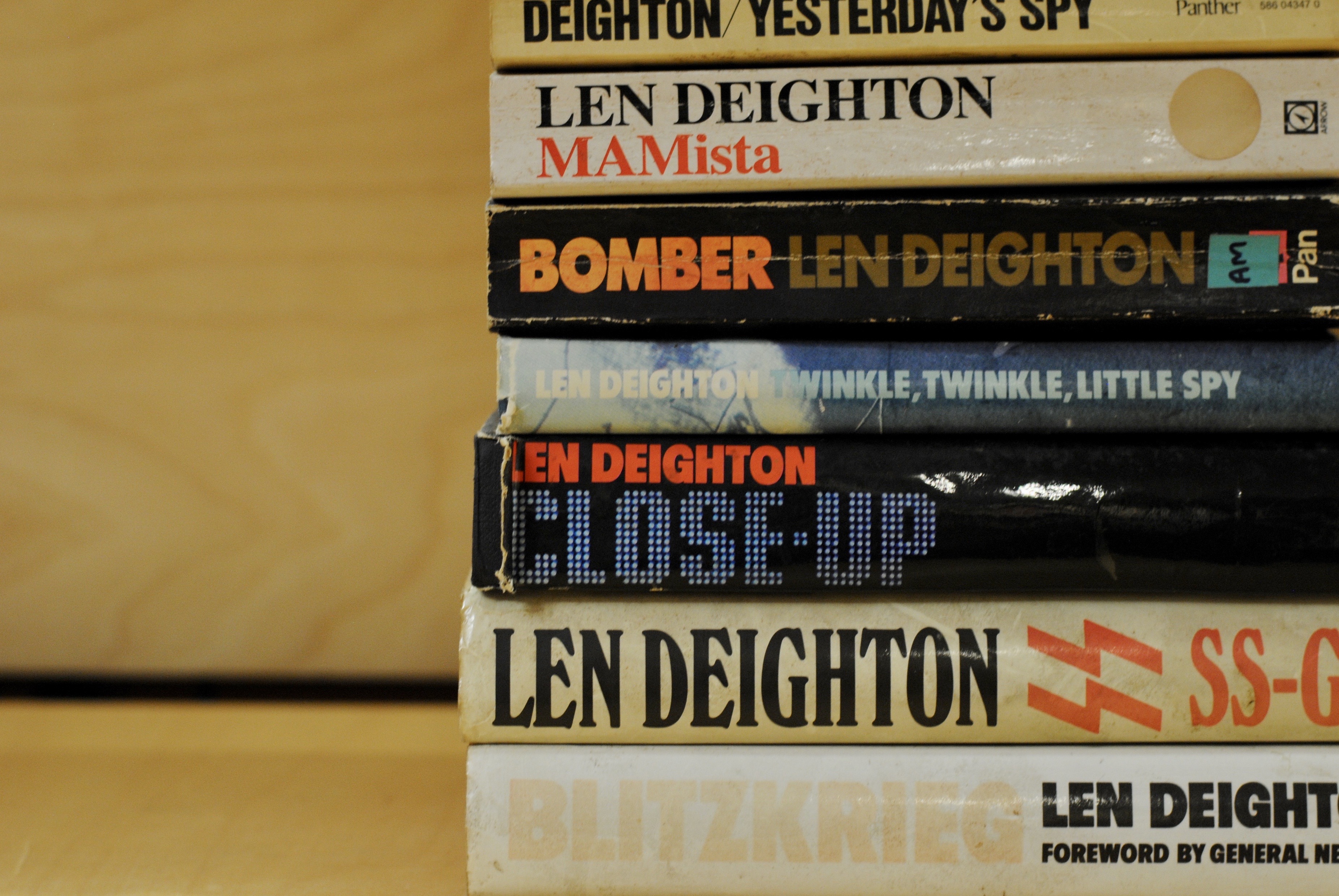

Burgess’s library at the International Anthony Burgess Foundation reveals that he read at least thirteen of Deighton’s books, including Close Up (1972), Twinkle Twinkle Little Spy (1976), XPD (1981) and MAMista (1991). While Burgess attempted to write his own spy novel, Tremor of Intent (1966), it may be that Deighton’s writing influenced him in different ways. Burgess writes that Deighton’s fiction has the power to ‘bring the dead back to life’ through ‘documentary’ technique. It is possible that Burgess was thinking of this aspect of Deighton’s work when he was writing historical novels such as Kingdom of the Wicked (1985) and Any Old Iron (1989).

What Burgess’s life-long love of Deighton’s work shows is the breadth of his literary interests. The letter itself offers another example of the support Burgess gave to the writers who impressed him, regardless of genre or subject matter.