Object of the Week: The Marx Brothers

-

Graham Foster

- 19th June 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

The library at the Anthony Burgess Foundation often reveals unexpected preoccupations and cultural connections. Alongside the more literary titles are several books about showbusiness, including biographies of David Niven, Sir Lew Grade, Jayne Mansfield, and Josephine Baker.

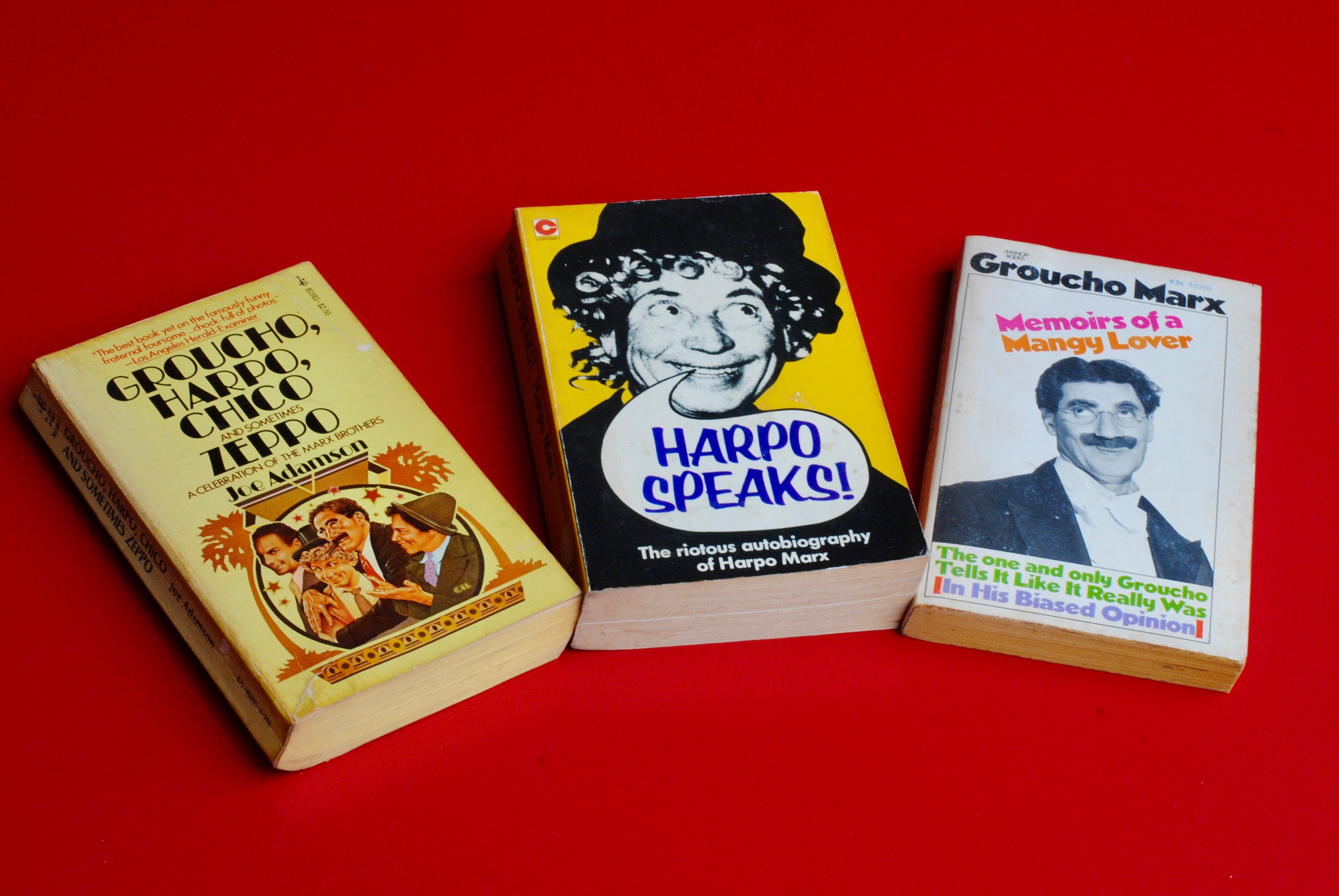

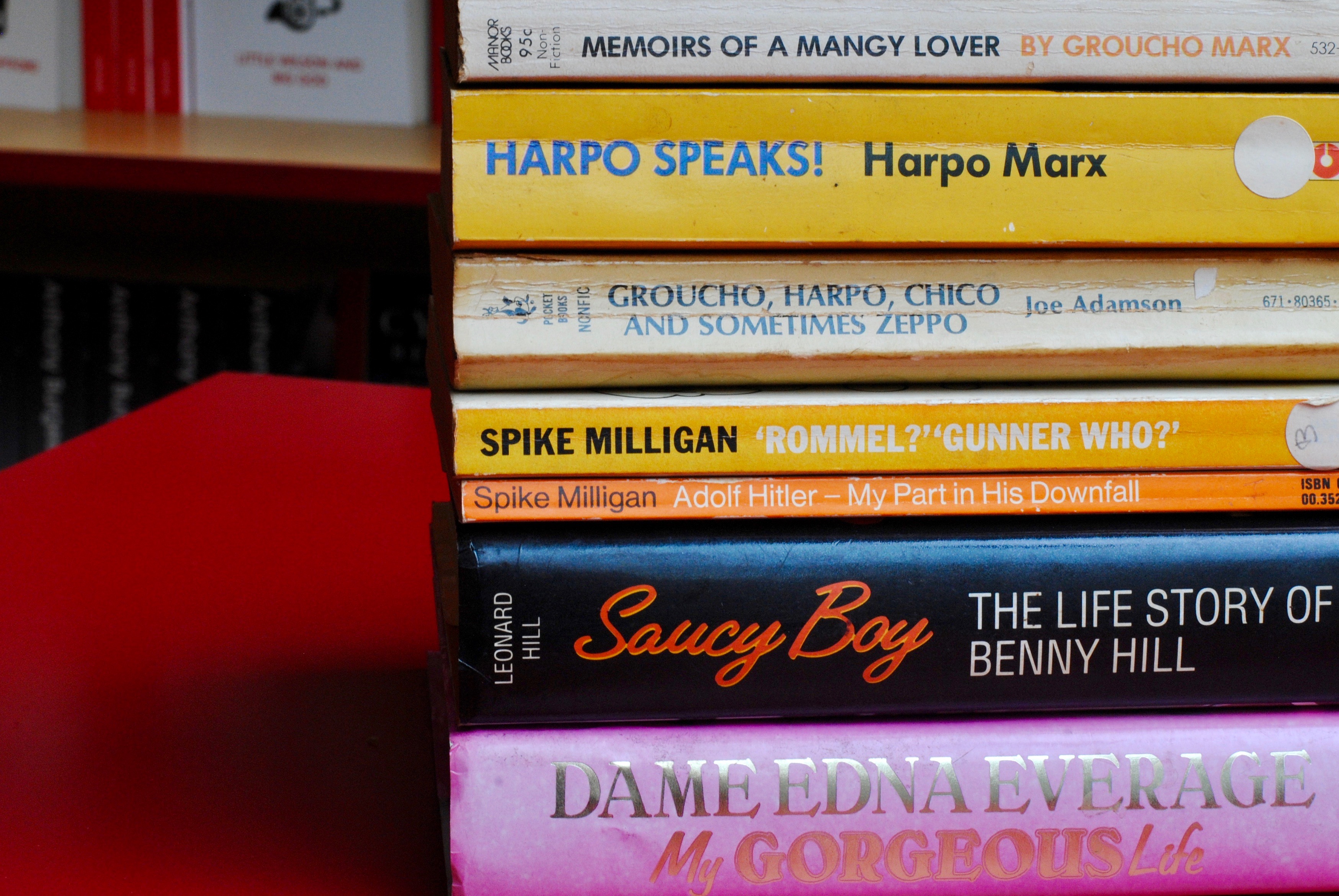

Burgess’s interests in film, performance and popular culture were varied, but he had a particular affection for comedy. This is shown in his collection of books about the Marx Brothers: Memoirs of a Mangy Lover by Groucho Marx, Harpo Speaks by Harpo Marx, and Groucho, Harpo, Chico and Sometimes Zeppo, a biography by Joe Adamson.

Burgess’s fascination with the Marx Brothers is documented in various places. For example, when he was invited to curate a film season for the National Film Theatre in London in 1984, one of his choices was A Night at the Opera (1935). In the programme, he writes: ‘I love the Marx Brothers as the most flamboyant expression of dissidence that the West has ever known, and I think that this is the best thing they ever did. There is a classic scene (the one in which a ship’s cabin is turned into a black hole of Calcutta) whose comic ingenuity has never been matched.’

In 1972, Burgess was promoting A Clockwork Orange at the Cannes Film Festival when he met Groucho Marx at a formal lunch party where, as Burgess writes, ‘the guests were mostly intellectual Parisians […] who were more concerned with the structuralist and semiotic content of A Night at the Opera than with the rollicking fun that had never aroused their laughter.’

Of the comedian himself, Burgess remembers: ‘Groucho had come with the notorious girl who was to claim, four years later, the bulk of his estate. She kept saying “Aw, cut it out, Grouch,” whenever he sang bawdily’. Groucho had literary interests of his own, and maintained a correspondence with T.S. Eliot. The two later met, and started a rather antagonistic friendship, in 1964. Burgess remembers that Groucho quoted T.S. Eliot at their meeting, only to be told ‘Aw, cut it out, Grouch’.

The evening spent in Groucho’s company was a pleasant one for Burgess, and he recalls it as a high point of his visit to Cannes. Groucho, he says, ‘was spontaneously witty, but not above filing away the occasional unpurposed crack. It was on this occasion that a lady was mentioned who had ten children because she loved her husband. “I love my cigar,” Groucho said, “but I take it out sometimes”.’

The meeting ended with Groucho giving Burgess a Romeo y Julieta cigar, which Burgess attempted to save as a keepsake because he ‘considered it too precious to smoke. Somebody else smoked it when my back was turned’.

Burgess’s had an avid interest in comedy, and his collection of books runs from the literary, with comic novels by the likes of Evelyn Waugh and Kingsley Amis, to the more unexpected, with biographies of comedians including Lenny Bruce (whose ‘sexually explicit’ style of comedy Burgess blames for superseding the music hall), Spike Milligan, and Dame Edna Everage.

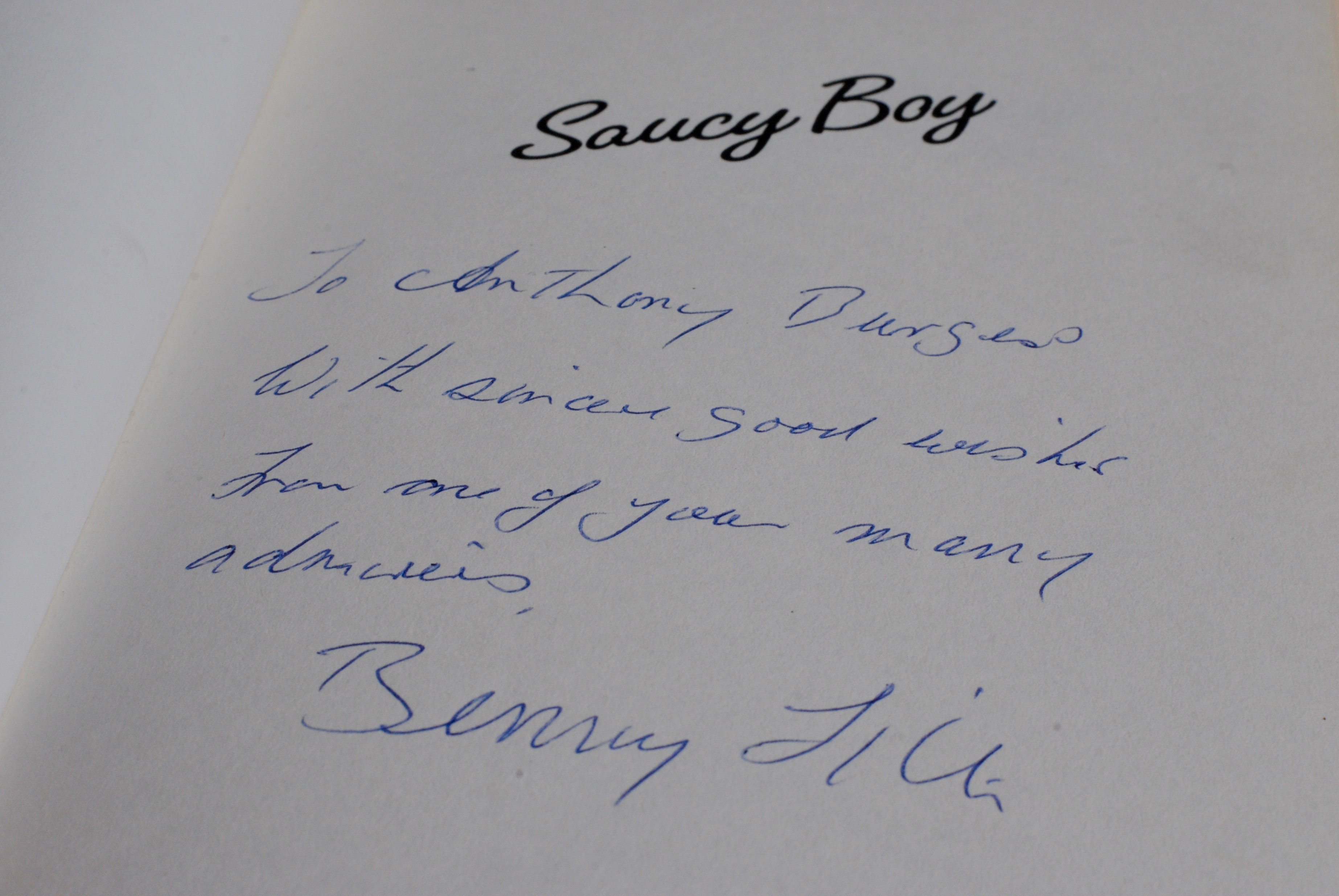

The archive at the Foundation also contains items relating to Burgess’s friendship with Benny Hill, such as signed photographs and correspondence (the latter signed, ‘That nice Benny Hill’). Burgess admired Hill’s television shows, which he desribed as ‘the comedy of sexual regret’. He disagreed with the criticism that Hill’s comedy was exploitative, preferring to see it as having been inspired by the music hall, where both of Burgess’s parents had worked. He writes: ‘Benny’s sauciness is cognate with that of the old seaside postcards’. He calls on critics to ‘quell their superior disgust at bosoms and lavatories and celebrate one of the great artists of our age’. Burgess’s admiration of Benny Hill led to an invitation (which he accepted) to deliver a eulogy at the comedian’s memorial service in 1992.