Object of the Week: Rituale Romanum

-

Graham Foster

- 6th December 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

In the Burgess Foundation library there is a small collection of the religious texts, including several bibles, the Quran, and several histories of world religion. Among these books is a small volume bound in scuffed leather titled Rituale Romanum. This book contains the Rites of the Roman Catholic Church, and is entirely in Latin. Burgess’s edition was published in 1881, but it is not known how it came to be in his collection. The only clue to its origin is the monogram on the cover: G.A.

Rituale Romanum is split into ten sections, each dealing with a different Roman Catholic rite, including: the administration of general sacraments; the Baptism rites; the Sacrament of Penance; the Eucharist; the rites for anointing the dying; the funeral rites; the marriage rites; general blessings; processions; and the exorcism of those possessed by a demon. The Rituale Romanum is used by priests during services and sermons, and is one of the three official volumes of the procedures of Catholic worship (along with the Missale Romanum and the Breviarium Romanum).

Burgess would have been familiar with some of these rituals from his childhood in both the Catholic Church and during his schooldays at Xaverian College, and this book inspired some of his later writing. Most notably, Earthly Powers (1980) contains a scene in which, Philip, a British man in Malaya, putatively possessed by demons, undergoes the exorcism ritual conducted by Monsignor Carlo Campanati.

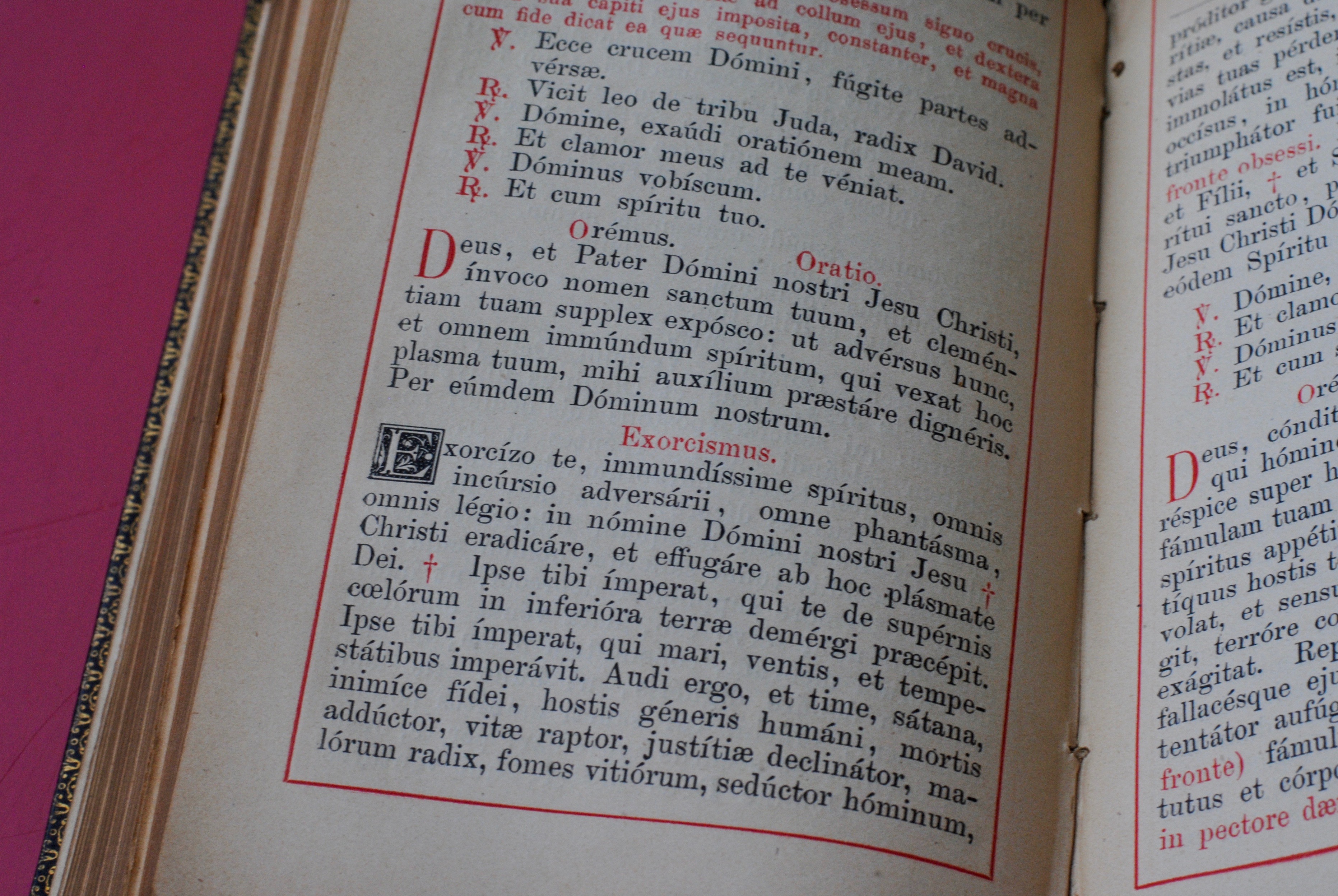

In the exorcism scene, in Chapter 38 of the novel, Burgess quotes directly from the Rituale Romanum. Carlo uses the address extracted from Luke 11: ‘Omnipotens Domine, Verborum Dei Patris, Christe Jesu, Deus et Dominus universae creaturae…’ (‘Almighty Lord, Word of the Father, Jesus Christ, the Lord of All Creation…’). Burgess also takes the congregation’s responses to the address, with Kenneth Toomey saying: ‘Ecce crucem Domini, fugite partes adversae’ (‘Behold the sign of the cross, flee to other places’), and ‘Vicit leo de tribu Juda, radix David’ (‘The Lion of the Tribe of Judah, the Root of David’). Unfortunately, the exorcism does not work.

Burgess’s use of this edition of the Rituale Romanum is confirmed a few pages later, when Carlo ‘opened his book at page 366. Crossing and crossing with his right hand, book in left, he growled out the liturgy. “…Audi ergo, et time, satana, inimice fidei, hostis generis humani, mortis adductor, vitae raptor, justitae declinator, malorum radix, fomes vitorum, seductor hominum, proditor gentium, incitator invidiae, origo avaritiae, causa discordiae, excitator dolorum…”’ (‘…Therefore hear and fear, Satan, enemy of the faith, the enemy of the human race, bringer of death, of life, deviant of justice, turn away, root of all evil, the tinder of vices, seducer of men, betrayer of nations, inciter of envy, origin of avarice, cause of discord, bringer of sorrows…’ This liturgy appears on page 366 of the copy of the Rituale Romanum in the library at the Burgess Foundation.

This is not the only exorcism in Burgess’s fiction. In The Eve of Saint Venus, written in 1951, the protagonist Ambrose Rutterkin, places a wedding ring on the finger of a statue of Venus on the eve of his marriage. The statue comes alive and encloses the ring in a stony fist. In order to expunge the ghost of Venus from the house, the Anglican Reverend Norman Chauncell is called to perform the appropriate rites. Chauncell is a typically Burgessian character: a Vicar who enjoys his brandy, and maniacally sees evil everywhere, even in the birds, which he claims are ‘Devils in the guise of birds’. He uses the same pages of the Rituale Romanum to expel the spirit as Carlo Campanati does in Earthly Powers, which suggests that Burgess owned a copy as early as 1951.

The most famous fictional representation of an exorcist is in William Peter Blatty’s 1971 novel The Exorcist, adapted into a film in 1973 by William Friedkin. Given his interest in the rituals of the Catholic Church, it is not surprising that Burgess wrote about the novel in the New York Times. Although he reviews the novel positively, he notes that the devil ‘defies the exorcising Jesuits – perhaps because the ritual is conducted in the vernacular and the enemy is notoriously conservative?’ Burgess’s fictional exorcisms both appear in the original Latin, and he mildly rebukes Blatty for this lack of authenticity. Nevertheless, the Rituale Romanum is the common thread that links all of these works, and remains an important object when attempting to understand Burgess’s relationship with his Catholic faith.