Object of the Week: The Week-End Book

-

Graham Foster

- 22nd November 2017

-

category

- Object of the Week

The Week-End Book, published by the Nonesuch Press in June 1924, was a staple of British households in the first half of the twentieth century. Its popularity was such that it went through eighteen impressions up to 1927, and between October 1928 and October 1930 it sold more than 52,000 copies.

The book itself is an almanac of literature, songs and activities to occupy a family during their weekend downtime. Its remit is particularly broad, with chapters on such subjects as: Poetry (Great Poems, Hate Poems and State Poems); Bird Song at Morning; Travels with a Donkey; The Law and How You Break It; First Aid in Divers Crises; and, for completion’s sake, A List of Great Poems Not in this Book. On the endpapers there are gaming boards for Draughts and Nine Men’s Morris.

The Week-End Book includes a selection of writings by authors including Ralph Waldo Emerson, William Blake, Robert Browning, G.K. Chesterton, Lord Byron, Samuel Coleridge, Robert Louis Stevenson, Aldous Huxley, William Wordsworth and Walter Raleigh.

The poems included in the almanac include very well-known verses, such as Shakespeare’s Sonnet CXXX (‘My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun’), John Donne’s ‘The Sun Rising’, and Andrew Marvell’s ‘To His Coy Mistress’. There are folk poems on subjects such as love and drinking, and contemporary poems of the 1920s such as Edith Sitwell’s ‘The Little Ghost Who Died for Love’ and ‘Lost Love’ by Robert Graves. There are patriotic poems about the Royal Family, celebrating the birth of Mary, Princess Royal (the daughter of King George V), and commemorating the death of King Edward VII, and there are many poems about the First World War.

The songs provide light relief, being mostly folk songs often with bawdy lyrics such as: ‘Mademoiselle From Armentieres’ (or ‘Two German Officers Crossed the Rhine’); ‘Spanish Ladies’; and ‘O, Me Taters’. The musical direction reveals that these songs are variously to be sung ‘with inebriation’, or ‘roisterously and in march time’.

These songs appear alongside more traditional selections such as: ‘Greensleeves’; ‘Shenandoah’; ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot’; and ‘Sumer is Icumen In’. Many of the songs are selected with families in mind, and the music for traditional rounds such as ‘Frere Jacques’.

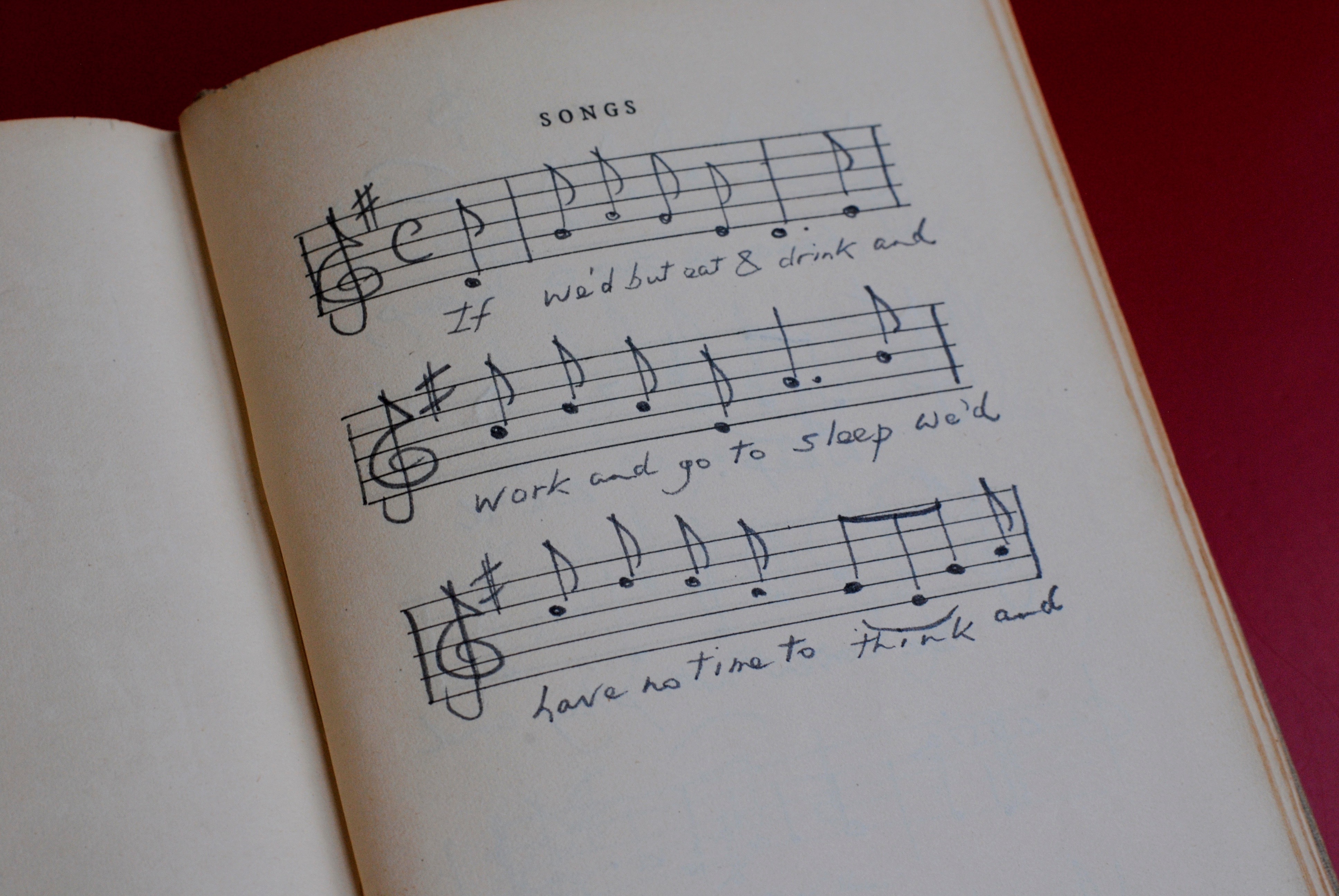

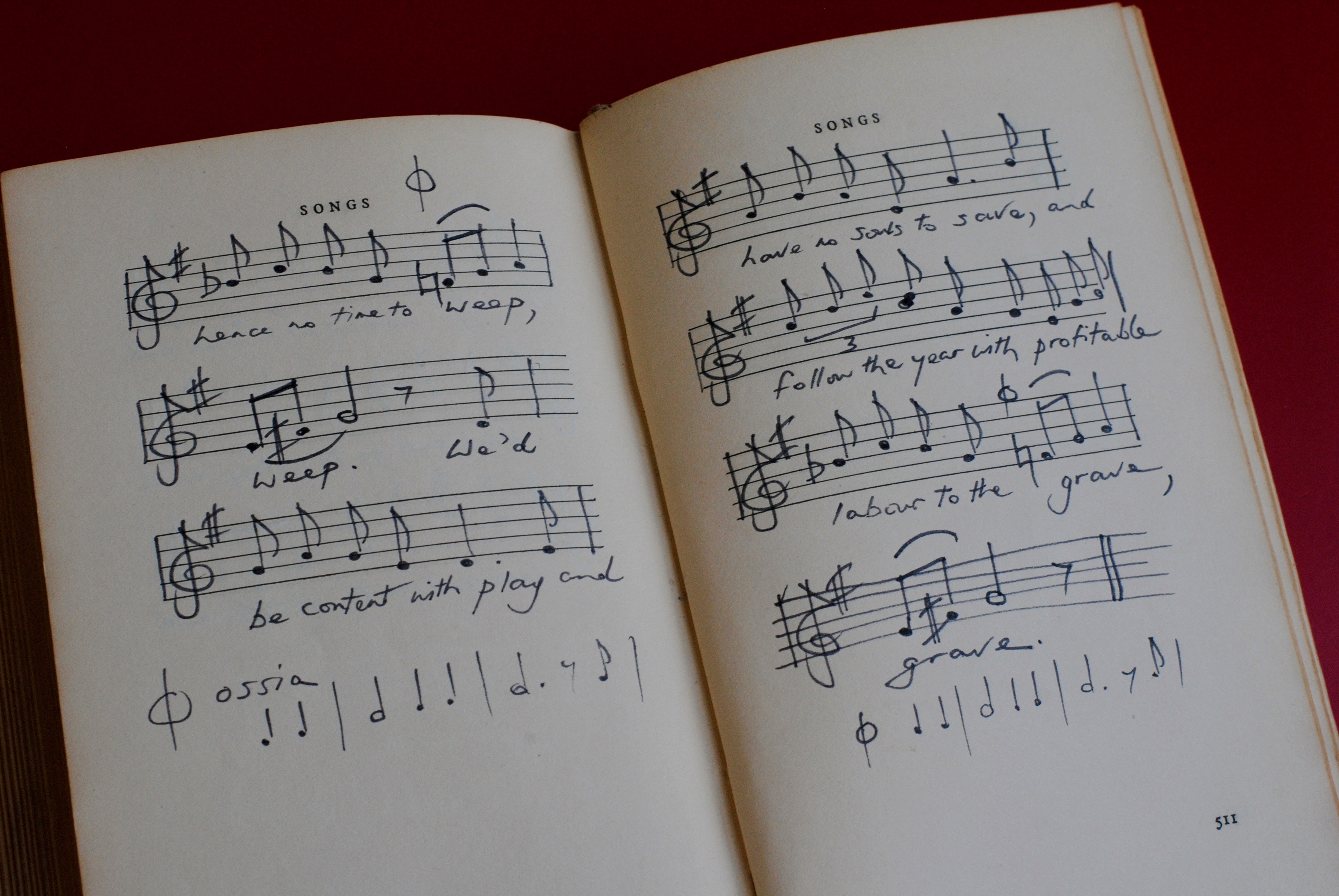

This copy of The Week-End Book found its way into Burgess’s possession at some point after 1977, as the previous owners have inscribed their names on the title page. The final section of the book contains musical staves for the reader to compose new music. Being a composer, Burgess has seized this opportunity and written an original piece of music with lyrics:

If we’d but eat and drink and

Work and go to sleep we’d

Have no time to think and

Hence no time to weep,

Weep.

We’d be content with play and

Have no souls to save, and

Follow the year with profitable

Labour to the grave,

Grave.

This short piece appears to be an early draft of a song which appears in A Dead Man in Deptford (1993). In the novel, which follows the adventures of the playwright Christopher Marlowe, the song appears as a piece of tavern entertainment, partly written by Captain Fortescue (a disguised Jesuit priest) and completed by Marlowe. In the novel, it reads:

Fortescue:

If we’d but eat and drink

And swink and so to sleep

There’d be no time to think

And hence no time to weep.

Marlowe:

We’d be content with play

And have no souls to save

And follow the year with profitable

Labour to the grave.

The novel gives no indication of the tune, but The Week-End Book shows that Burgess composed the music (including percussion on the ‘ossia’ or bones) to go along with these words. This music, which never been performed, has remained hidden in the back of this odd almanac in Burgess’s library until now.