More on ‘That the Earth Rose Out of a Vast Basin of Electric Sea’

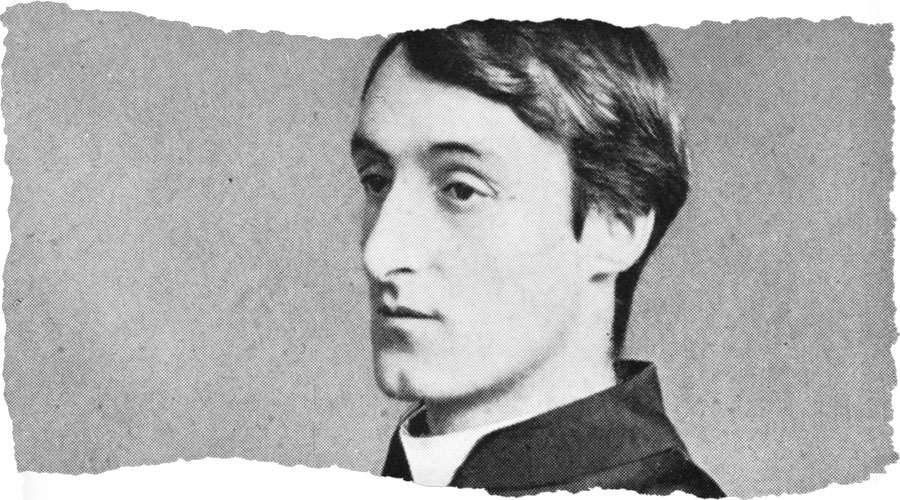

‘That the Earth Rose Out of a Vast Basin of Electric Sea’ was Burgess’s debut published poem. Appearing in his school magazine The Electron, it was one of a number of poems consciously in the manner of Gerard Manley Hopkins that Burgess composed as a teenager: Hopkins would go on to be one of the major influences on Burgess’s writing throughout his life.

Writing a tribute to Hopkins for his centenary in 1989, Burgess claimed rather implausibly that he had first read Hopkins’s poetry sailing back from France to England in 1930 aged thirteen, returning from a school trip; Joyce’s Ulysses, then prohibited, was smuggled in the waistband of his shorts. This memory does not appear in his autobiography, and whatever the truth of the story Burgess conveys the urgency and excitement he felt reading the works of these writers for the first time.

Elsewhere Burgess picks out Hopkins’s poem ‘Pied Beauty’ as one that began what he described as his lifelong devotion to his work: listen to him reading it here.

Burgess was animated by the linguistic and rhythmic freedom that Hopkins permitted, with his use of compound words such as ‘larkcharmed’ or ‘cuckooechoing’ (from Hopkins’s most famous poem ‘The Windhover’, or kestrel), alliteration, and stressed rather than syllabic lines all giving prominence to what Burgess saw as ‘the Teutonic element in English’, its authentically expressive Anglo-Saxon roots.

Hopkins’s devout and troubled relationship with his faith also spoke to Burgess as a young man, as Burgess worked out his own complex relationship with the Catholic Church of his birth; as did Hopkins’s deeply felt and earnest love poetry, which the adolescent Burgess was keen to emulate.

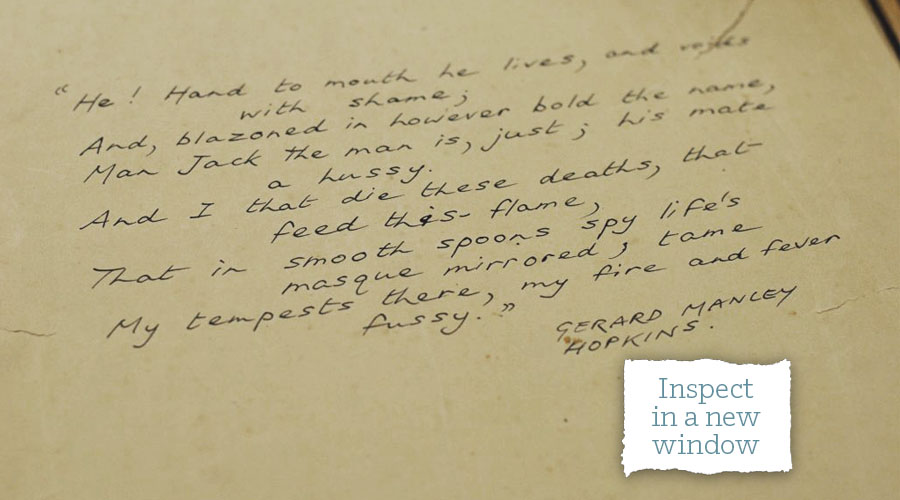

Poetry by Hopkins later appears in the epigraphs to Burgess’s music, such as his ‘Sonata for Violoncello and Piano in G Minor’, composed in 1945; and in his fiction with references to Hopkins appearing unexpectedly in novels.

Nadsat, Burgess’s invented language from A Clockwork Orange, is made from many sources, including Russian, Elizabethan English, and rhyming slang, but Hopkins is there too: when Alex laments his fatigue, he states he is ‘shagged and fagged and fashed’ which is derived from Hopkins’s dramatic poem ‘The Leaden Echo and the Golden Echo’:

‘Oh why are we so haggard at the heart, so care-coiled, care-killed, so fagged, so fashed, so cogged, so cumbered.’

And in The Clockwork Testament, Burgess’s poet-hero Enderby attempts to adapt Hopkins’s long poem The Wreck of the Deutschland into a film, but is undone by philistine movie-makers.

Here is the epigraph to ‘Sonata for Violoncello and Piano in G Minor’, in Burgess’s own hand.

Burgess attempted to adapt The Wreck of the Deutschland himself, setting it to music for orchestra and singers: this ambitious piece has never been performed. In 1989 Burgess wrote a radio adaptation of St Winefred’s Well, an unfinished play by Hopkins, broadcast on BBC Radio 3. Concluding his centenary appreciation of Hopkins, Burgess wrote:

‘We live in an age of dilution. Hopkins brews the powerful liquor of faith – in God, also in language.’

Listen to Burgess reading ‘Tom’s Garland’ by Hopkins below. And then explore more Anthony Burgess and Poetry.