More on ‘In This Spinning Room’

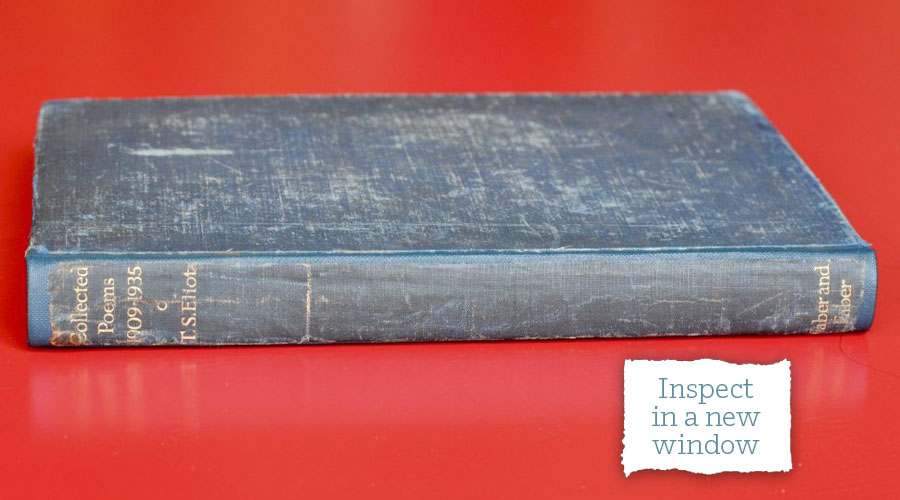

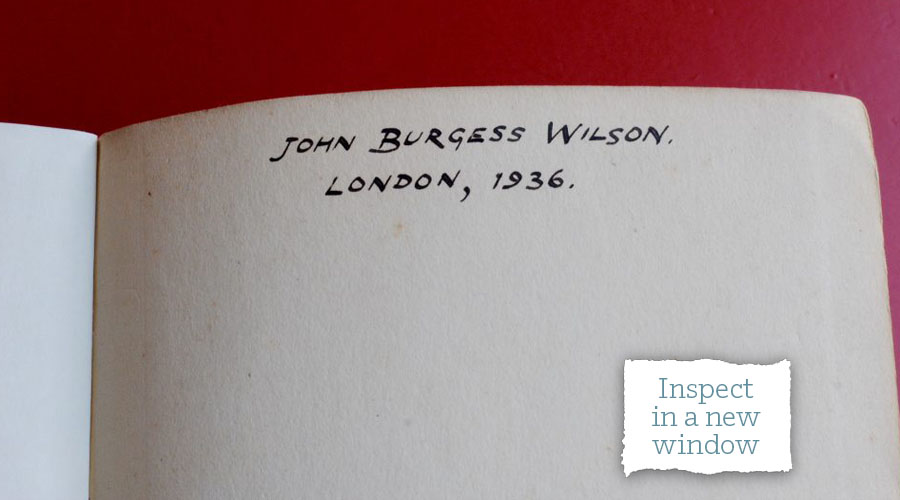

In 1936, Burgess read T.S. Eliot’s Collected Poems on a train journey from London to Manchester. He already knew Eliot’s The Waste Land, having borrowed it from the public library while at school, and Eliot was already becoming an important influence.

In 1971 Burgess recalled his first reading of The Waste Land:

I was only fifteen, and understood very little of the poem, but I recognised that it was important. I seemed to hear a door a long way down one of my mind’s corridors, trying to creak open but not quite making it. […] I copied the whole poem out; then I got down to learning it by heart.

By the time Burgess enrolled at Manchester University in 1937, he said, ‘I understood The Waste Land pretty well. Without boasting, I can say that I knew the poem better than any of my English lecturers: they did not have it by heart, and I did.’

And Burgess acknowledged the influence of Eliot on his early novels: ‘It was, I discovered myself when I first began to write seriously, hard to get the Eliotian voices out of my ears and my prose. It was so delightful to conjoin mock-pomposity with deliberate vulgarity, to throw in recondite literary allusions for ironic effects, to make statements conveying an authority somehow both professorial and parsonic, and yet, at the same time, tinged with self-mockery.’

Burgess was particularly excited by the dramatic and musical possibilities of Eliot’s writing. His first attempt to set Eliot’s poetry to music took place on a train journey from London to Manchester in 1936: ‘I took music manuscript paper from my suitcase and sketched settings of the songs in Sweeney Agonistes.’

When Burgess directed an amateur production of Sweeney Agonistes in Adderbury in 1951, he used his own settings of the songs and accompanied the cast at the piano. He performed these Sweeney songs again in 1980 — as part of the T.S. Eliot Memorial Lectures. Listen to him singing them on this slightly scratchy recording here:

In April 1978 Burgess set The Waste Land to music for narrator, soprano, flute, oboe, cello and piano. Following the collage technique he found in Eliot, Burgess uses quotations from opera and classical repertoire and fragments of popular songs, to create a rich and allusive tapestry. Eliot’s text is declaimed over a gentle, sonorous background, interspersed with moments of action and drama — rather like a film soundtrack.

In fact, Burgess wrote that he sometimes thought of the poem as ‘a film scenario, which in many ways it resembles — with its jump cuts and flashes backward and forward and montages and intense economy — [more so] than anything by Truffaut or Godard or Fellini or Antonioni.’

Burgess’s only contact with T.S. Eliot came in the 1950s, when he submitted a collection of his early poems to Faber & Faber, where Eliot was poetry editor. He received a polite rejection (now lost), but Burgess was delighted that his poem ‘In This Spinning Room’ and two others were ‘mildly approved’ by Eliot, who indicated his mild approval with pencilled ticks on the manuscript. Burgess recalls this episode in his memoir, Little Wilson and Big God.

His obituary essay for Eliot, published in the Listener in January 1965 and titled ‘Lament for a Maker’, articulates some of the ways in which Eliot influenced his writing:

[Eliot] was a maker in a double sense: he made not only his poetry but also the minds that read it. With great patience he schooled us away from shock or bewilderment towards acceptance, eventually love, of his work. Love became a habit. In time, the Eliotian cadences, whether verse or prose, turned into our instinctive music.

Explore more Anthony Burgess and Poetry.