Editing ABBA ABBA

-

Paul Howard

- 18th February 2019

-

category

- Blog Posts

If Beard’s Roman Women is an odd book, ABBA ABBA, the other half of Burgess’s reaction to his time in Italy in the 1970s, is perhaps even odder still. The book is divided into two sections: Part One is a short historical novel of sorts, while Part Two consists mainly of poems translated into English by Burgess. These two seemingly separate elements are brought together by a curious bridging piece in which Burgess blends fact, fiction, and poetry. Very few of the book’s reviewers at the time knew quite what to make of it, with one rightly asking: ‘What is Burgess up to now, then?’

Part One is set in Rome in the winter of 1820-1 where a consumptive John Keats has finally arrived with his travel companion Joseph Severn to convalesce on doctor’s orders in the milder climes of the Eternal City. Whilst in Rome, Keats meets the Italian poet Giuseppe Gioachino Belli through a bilingual intermediary. They discuss poetry, naturally, from the differing viewpoints of their two cultures.

Part Two fast-forwards to the present day, explaining what became of Keats, Belli and their interpreter. It then presents 71 of Belli’s Roman sonnets – he actually wrote 2279 in total – in the unedited translations, we’re told, of a descendent of the Keats and Belli interpreter. By a quirk of fate, the descendent was a Mancunian and so the poems are translated into ‘English with a Manchester accent’.

As the title suggests, the book is broadly about poetry, though it has plenty to say about other major themes including life, death, sex and religion, and the place of art among them. ABBA ABBA is the usual rhyme scheme of the first part of a Petrarchan sonnet, the high poetic tradition in which Belli wrote his huge corpus of poems. Crucially, though, his poetry was built on a fundamental twist: instead of lofty subjects in the usual language of Italian literature, Belli voiced the Roman underclass of his day and all their preoccupations in their own demotic Roman dialect. The content is frequently comic, bawdy and blasphemous. This paradox delighted Burgess, and the book explores ways of telling it to a wider audience.

I first came to work on Burgess when writing my doctorate on Belli’s poetry in the Italian department at the University of Oxford. Before that I’d had a go at translating Belli’s Roman into a version of my own native Yorkshire dialect. Initially, Burgess was the only translator I could find into any kind of English. But even as a Belli devotee, I wasn’t sure at all what Burgess was up to in this odd book which claimed the sonnets in Part Two had been translated by somebody called J.J. Wilson. So, as a sideline, I visited the Anthony Burgess Foundation in 2011 to look at the primary materials relating to ABBA ABBA, wondering if Burgess had left behind any notes that might shed light on how he’d discovered the Roman poet.

Having looked through some diaries and correspondence, a couple of sketches, a few drafts of the Belli poems and a pad of crib translations – literal renderings of the sense in English prose – in a different hand (definitely not Burgess’s, and not his wife’s either), I came to a few conclusions: 1. Burgess’s wife Liana hadn’t done any of the Belli translations at all, contrary to what I’d read in more than one source; 2. the translated poems matched the sonnets in a particular anthology of Belli’s biblical poems; and 3. Burgess must have written ABBA ABBA as a means of getting his versions into print. I wrote an article on my findings, and carried on with Belli.

More materials relating to Belli emerged at the Burgess Foundation in the meantime, including an essay by Burgess on the problems he encountered in translating the Roman sonnets into English. The Times Literary Supplement published the essay in full, with an accompanying piece I wrote to explain the context, to mark the Burgess centenary in February 2017. This essay is one of five by Burgess on his experience of Rome and translation which feature in the appendices to the new edition, along with Burgess’s draft workings for the final poem in the book.

Editing ABBA ABBA involved consulting the original typescripts, now kept at the Harry Ransom Center in Texas. Additionally, I looked at various drafts of the poems as well as correspondence and contracts, held in the Burgess archives in Texas, Manchester and IMEC (Normandy). Providing explanatory notes to Part One was especially rewarding and involved deconstructing Burgess’s portrait of Keats. Other than the initial idea of having the two poets meet in Rome, a purely fictional device designed to juxtapose two very different cultural worlds, Burgess plucks very little out of thin air. Most of the setting is expertly crafted from biographical and literary sources. With Part Two I was on more familiar ground, but the edition provides a commentary on all the poems, both as translations of the original Roman dialect texts and as Burgess poems in their own right.

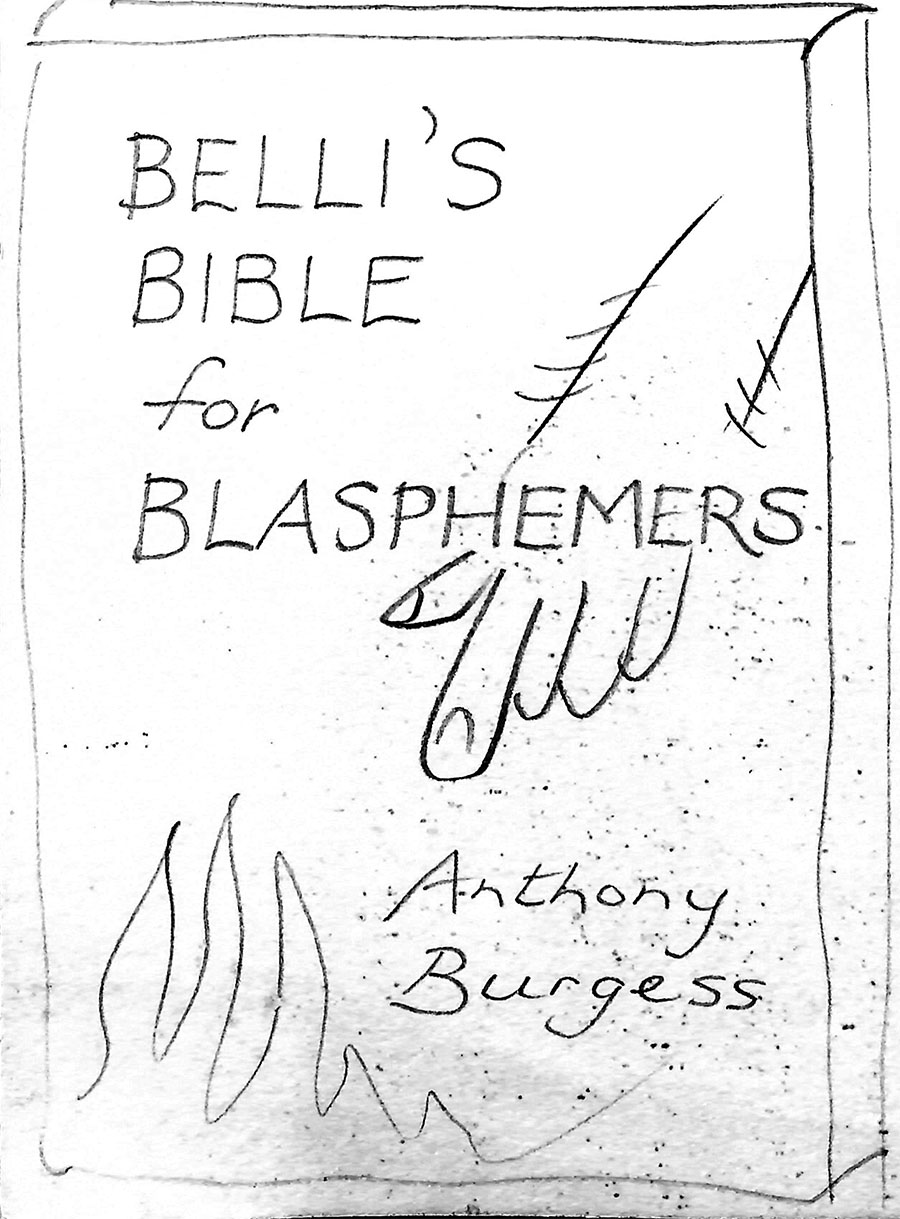

Some of the other discoveries I made by studying the documents were surprising. Part One was definitely written after Part Two, for instance, and I talked to the linguist who produced the cribs which Burgess used to write his versions of the poems. I found that Burgess also wanted to issue Beard’s Roman Women and ABBA ABBA as a single book at one stage, which might have changed how we know the texts today. Intriguingly, too, Burgess was advised by lawyers for his publisher (Faber) to change his original title for the novel (Belli’s Blasphemous Bible) on the grounds of potential blasphemy charges.

More than anything else, living with the texts and paratexts of ABBA ABBA has given me an insight into Burgess’s extraordinary creativity. The book stands as his tribute to two of Europe’s greatest modern poets in the figures of Keats and Belli, but it is ultimately more than that. It’s a musing on the genesis of literature and its journeying across perceived cultural frontiers. The book has been much overlooked and misunderstood, and I hope this new edition of ABBA ABBA goes some way towards improving its fortunes.

Paul Howard is Senior Teaching Associate in Italian at the University of Bristol and the editor of ABBA ABBA: The Irwell Edition, which is available now. For more information visit the Irwell Edition page at Manchester University Press.