Burgess and Shakespeare

Throughout his career, Anthony Burgess was fascinated by the writing and life of William Shakespeare. Explore these pages to find out about the influence of Shakespeare on Anthony Burgess, and the insights Burgess brings to our reading of his work.

- Burgess and Shakespeare

- Nothing Like The Sun

- Burgess's Shakespeare biography

- The Fictional Shakespeares of Anthony Burgess

- The 1973 Shakespeare Lectures

- Burgess's Shakespeare music

Burgess’s Shakespeare biography:

hakespeare is Anthony Burgess’s speculative biography of the Bard. Burgess claims in his foreword ‘the right of every Shakespeare-lover who has ever lived to paint his own portrait of the man’, and he does this with characteristic colour and vigour.

hakespeare is Anthony Burgess’s speculative biography of the Bard. Burgess claims in his foreword ‘the right of every Shakespeare-lover who has ever lived to paint his own portrait of the man’, and he does this with characteristic colour and vigour.

Like every biographer of Shakespeare, Burgess is forced to rely on conjecture, due to the limited facts known about the playwright’s life. First published in 1970, the book draws on Burgess’s thwarted attempts to write a film about Shakespeare’s life. Its lavish illustrations are matched by extravagant and sometimes fanciful descriptions of the Elizabethan age.

Stanley Wells identifies the interaction between the imagination of Burgess the contemporary novelist and Shakespeare the Elizabethan dramatist as being at the heart of this book. Shakespeare is perhaps at its most convincing in its treatment of the plays.

Burgess offers detailed commentaries on Troilus and Cressida, Hamlet, and Richard III, writing in his didactic and inspiring teacherly manner. He is not shy of dismissing Love’s Labour’s Lost, King John and Pericles — which is said to be ‘the worst play of Shakespeare’s maturity’.

There are vivid speculations about Elizabethan life and politics, caricatures of figures from the stage and court, and a deep and personal identification with Shakespeare himself. These elements combine to give the biography its great liveliness and energy.

Get thee to: An introduction | Shakespeare illustrated | Stanley Wells writes | Another Shakespeare section (see links at top of page)

he first edition of Anthony Burgess’s Shakespeare contains 150 images, including paintings, woodcuts, engravings and photographs.

he first edition of Anthony Burgess’s Shakespeare contains 150 images, including paintings, woodcuts, engravings and photographs.

The pictures are accompanied by detailed captions, and although Burgess claims in his introduction that his words are less important than the pictures, the captions he wrote add to the rich flavour of this eccentric biography.

The dust jacket says: ‘In a richly illustrated narrative that delights with its wit and learned speculation, Anthony Burgess’s book captures the essence of a golden age and the spirit of a man of genius.’

A selection of scanned illustrations is presented here, with their original captions.

Above: Though printing in Shakespeare’s day could not hold a candle to our own, press-operators became powerful beacons of literacy.

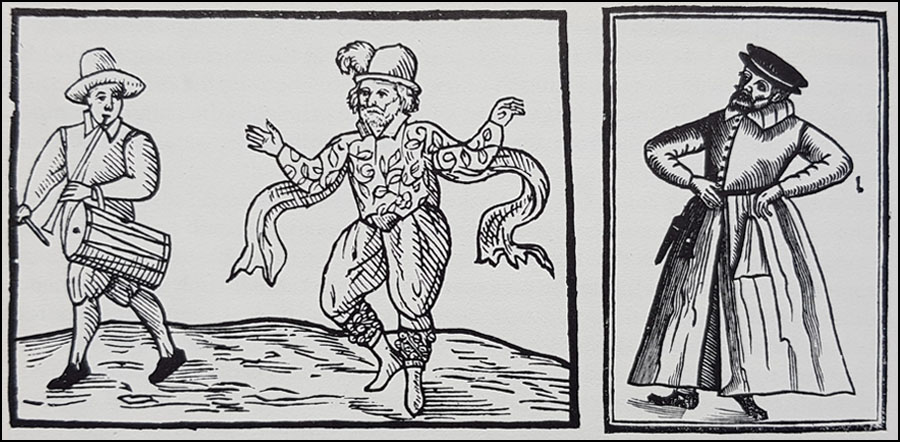

Above: (Left) William Kemp, the comedian, left Shakespeare’s company in a huff and danced a justification of himself from London to Norwich. He was replaced by (right) a more subtle comic, Robert Armin.

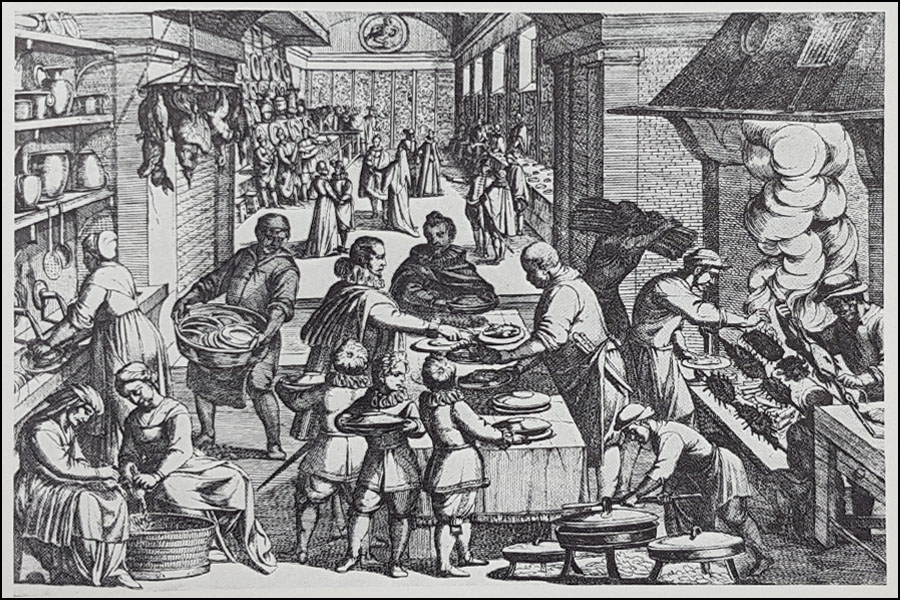

Above: However short in Vitamin C the diet of Shakespeare’s times may have been, preparing a meal was a ritual of much complexity.

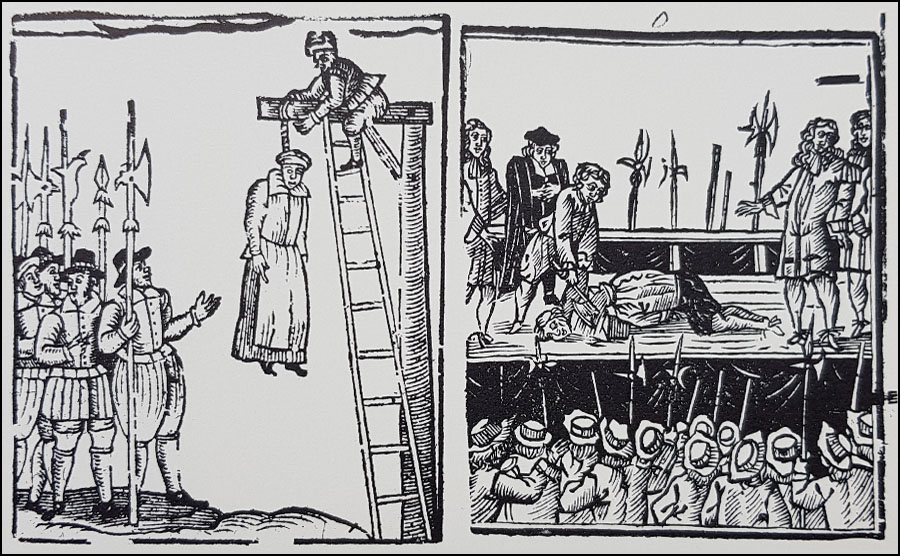

Above: Faintly comic woodcuts veiled the savagery of hanging, to be followed by drawing and quartering — that apotheosis of the executioner’s art. Nor did heads roll from the axe with the aplomb that this other elegantly witnessed execution might suggest.

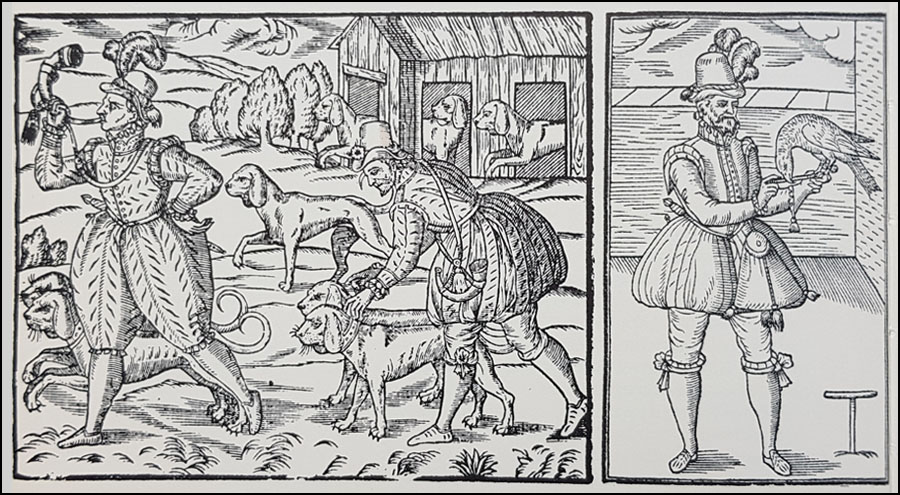

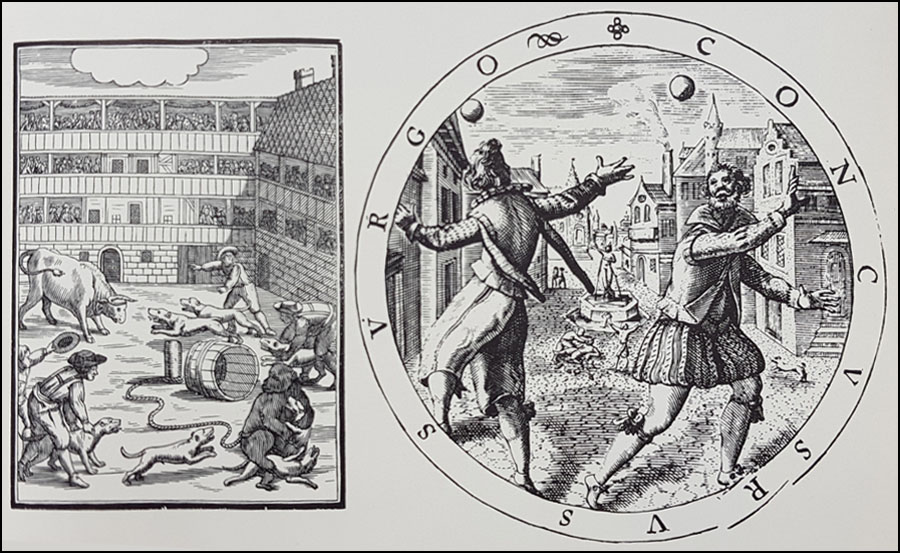

Both sets of pictures above: Hunting, hawking, animal-baiting and football — not the formal game of today but a gross and bloody purging of excess energy — were among the sports with which the Elizabethans refreshed their zest for life.

Get thee to: An introduction | Shakespeare illustrated | Stanley Wells writes | Another Shakespeare section (see links at top of page)

ere is an extract from Stanley Wells’ introduction to the most recent edition of Shakespeare, produced by the Folio Society and reprinted here by kind permission of the author.

ere is an extract from Stanley Wells’ introduction to the most recent edition of Shakespeare, produced by the Folio Society and reprinted here by kind permission of the author.

The materials available for a Shakespeare biography are, as Burgess admits in his foreword, ‘very scanty.’ Nevertheless, innumerable writers both before and after him have accepted the challenge, each of them finding different ways of augmenting and illuminating the documentary record. Though Burgess has no hesitation about bringing a novelist’s eye and imagination to bear upon the facts, he is frank about his inventiveness and punctuates his narrative with self-deflating comment on its more speculative fancies — ‘The whole of this paragraph is very unsound’ he writes, at the end of a discussion of the names of Shakespeare’s children which he disarmingly invites ‘the hard-headed reader’ to ignore; and ‘This fancy is of course unsound’, after imagining that Shakespeare portrayed himself as Christopher Sly in The Taming of the Shrew.

Seeking to illuminate the scanty biographical record Burgess, makes picturesque attempts to evoke the domestic environment in which Shakespeare lived and the sights and sounds of Elizabethan England. He offers aids to understanding such as a potted history of world drama up to the time of Shakespeare. He draws on his skill as a philologist to illuminate Shakespeare’s language, writing waggishly about spelling in the period: ‘To learne to wrytte doune Ingglisshe wourdes in Chaxper’s daie was notte difficulte.’ His awareness of the practical realities of the writing profession enables him to anticipate current theories of Shakespeare as a dramatist who often, especially in his early days, worked in collaboration with other writers: ‘The composition of Harry the Sixth, new in March 1592, must have been preceded by hackwork of various kinds — finishing plays started by others, brightening up old stuff with fresh topical references, throwing in new rhetorical monologues to swell the lungs of the star performer.’ In a major set piece in which he admits to giving his imagination free rein, he attempts to reconstruct an early performance of Hamlet, ‘the play which, of all plays ever written, the world could least do without.’ He picks up on the legend that Shakespeare played the Ghost of Hamlet’s father, linking the play with the supposedly recent death of the playwright’s own father and the less recent death of his son Hamnet, and also with national events — a play about Denmark written at a time when it was likely that the throne would soon be occupied by a king, James 1, with a Danish wife, and also seeing Claudius’s fear of Hamlet in relation to the danger that the Earl of Essex posed to Elizabeth: ‘How dangerous is it that this man goes loose!’ He persuasively suggests too that Essex’s noble bearing at his execution is remembered in Macbeth:

Nothing in his life

Became him like the leaving it; he died

As one that had been studied in his death

To throw away the dearest thing he owed

As ’twere a careless trifle.

Much of the attraction of this biography lies in Burgess’s highly individual, colourful, racy, Joyce-influenced prose style. He is often bawdy, finding ‘a nice low touch’ in the spelling Shagspere, quipping about ‘the galloping of four bare legs (there be some that say five)’ in the marital bed, and punning on Robert Greene’s description of Shakespeare as a ‘Johannes Factotum’ to make ‘Johnny Fatscrotum.’ His love of puns and complex wordplay frequently surfaces: writing of the teaching of Latin at the time, which was based on William Lily’s Short Introduction of Grammar prescribed for use in all grammar schools, he erupts into ‘School was grim. Those bottom-worn benches were no beds of roses, though Lilies lay on the desks.’ He indulges in paradox: on Troilus and Cressida, ‘Shakespeare left out the love, or rather purified it into lust.’ He can be tersely epigrammatic: ‘Latin, being already dead, could not die.’ And he can be simply wrong: when Susanna Shakespeare was accused of having ‘the running of the reins’ it does not mean ‘to wear the trousers at home’ but that she had a venereal discharge.

Much of the attraction of this biography lies in Burgess’s highly individual, colourful, racy, Joyce-influenced prose style. He is often bawdy, finding ‘a nice low touch’ in the spelling Shagspere, quipping about ‘the galloping of four bare legs (there be some that say five)’ in the marital bed, and punning on Robert Greene’s description of Shakespeare as a ‘Johannes Factotum’ to make ‘Johnny Fatscrotum.’ His love of puns and complex wordplay frequently surfaces: writing of the teaching of Latin at the time, which was based on William Lily’s Short Introduction of Grammar prescribed for use in all grammar schools, he erupts into ‘School was grim. Those bottom-worn benches were no beds of roses, though Lilies lay on the desks.’ He indulges in paradox: on Troilus and Cressida, ‘Shakespeare left out the love, or rather purified it into lust.’ He can be tersely epigrammatic: ‘Latin, being already dead, could not die.’ And he can be simply wrong: when Susanna Shakespeare was accused of having ‘the running of the reins’ it does not mean ‘to wear the trousers at home’ but that she had a venereal discharge.

In post-modern fashion, Burgess frames his narrative with a running commentary on his methodology: ‘This is the moment for the traditional florid cadenza to mark Will’s first glimpse of London. Very well, then.’ And there follows a picturesque evocation of the sights and sounds of the capital which ranges from well-informed paragraphs on music in both the streets and the plays, to thoughts about how ‘the known relish for brutality’ was ‘capable of being reconciled with the aesthetic instinct.’ It is genuinely illuminating to be told that when, after murdering Duncan, Macbeth speaks of his ‘hangman’s hands’, he ‘is not thinking of the manipulator of a rope: he is thinking of the fresh blood and the clotted entrails on fists that have plunged into the open belly of the victim.’

Although Burgess denies that his book is a work of literary criticism, he expresses a low opinion of some of the plays: Love’s Labour’s Lost is ‘a suety comedy’; King John is ‘the worst play of Shakespeare’s maturity;’ Pericles is ‘one of the worst plays he ever wrote.’ Yet he can be deeply perceptive on Shakespeare’s artistry. He has an acute defence of the relevance of the last act of The Merchant of Venice:

‘The play is about flesh and gold. Flesh is living and, through the music of love, capable of being transfigured above the muddy vesture of decay; gold is dead, but it breeds hate like maggots. Flesh cannot be weighted as gold can, and love, as Portia’s suitors find, cannot be evaluated as if it were a precious metal. Gold is redeemed when it is fashioned into a ring, symbol of marriage, and heaven itself does not then disdain to be thick inlaid with gold patines. On the level of narrative, the fifth act is redundant; on the level of symbolism, it completes a poetic statement.’

And the book is shot through with clever aperçus — ‘Hamlet is really about the impact on a Montaigne-like man of the harsh world of power and intrigue’: there speaks the former teacher — one can almost hear him adding the instruction ‘Discuss.’ On Clarence’s dream speech in Richard III: ‘For the first time . . . the unconscious mind is netted and landed.’ His book rises to genuine eloquence in the paradoxes of its conclusion:

‘We need not repine at the lack of a satisfactory Shakespeare portrait. To see his face we need only look in a mirror. He is ourselves, ordinary suffering humanity, fired by moderate ambitions, concerned with money, the victim of desire, all too mortal. To his back, like a hump, was strapped a miraculous but somehow irrelevant talent. It is a talent which, more than any other that the world has seen, reconciles us to being human beings, unsatisfactory hybrids, not good enough for gods and not good enough for animals. We are all Will. Shakespeare is the name of one of our redeemers.’

Get thee to: An introduction | Shakespeare illustrated | Stanley Wells writes | Another Shakespeare section (see links at top of page)