The Music of Anthony Burgess: Concerto for Pianoforte and Orchestra

Explore Burgess’s Piano Preludes and Concerto for Pianoforte and Orchestra below.

Listen to Preludes by Anthony Burgess, recorded by Richard Casey at the Engine House on Burgess’s own Bosendorfer piano.

An extract of the premiere of Concerto for Pianoforte and Orchestra in Eb by Anthony Burgess, performed by Gary Steigerwalt and the Pioneer Valley Symphony Orchestra in 1999.

Listen to Anthony Burgess read an extract from his novel The Pianoplayers, his novel inspired by the world of pianoplaying in Manchester and Blackpool in the 1920s and 1930s.

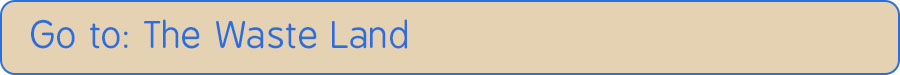

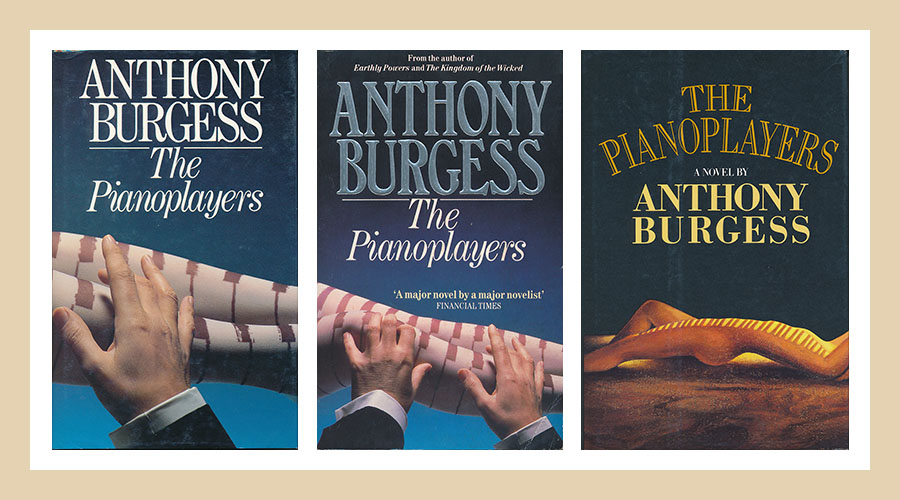

Anthony Burgess’s novel The Pianoplayers, first published in 1986.

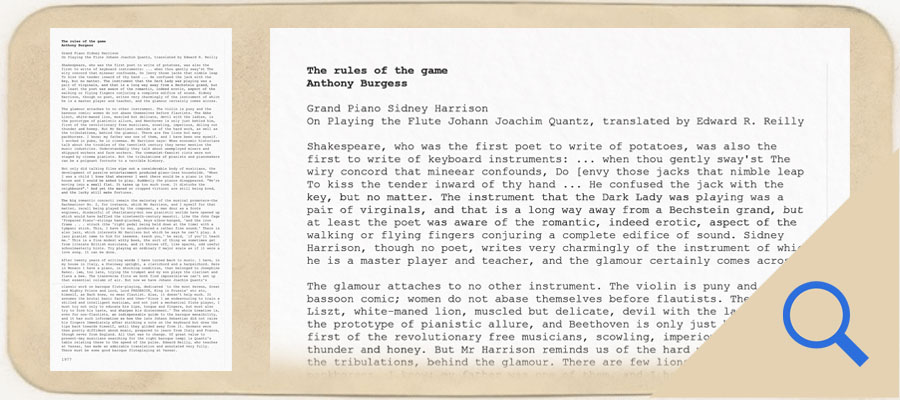

Burgess writes about the piano and the flute in this 1977 book review.

Preludes and Concerto for Pianoforte and Orchestra in Eb in context

The piano was at the heart of Anthony Burgess’s musical life. In the first volume of his autobiography, Little Wilson and Big God he describes his father Joseph, who gave Burgess his first and possibly his only musical instruction in the instrument:

My father, bowlered and ready for an evening’s heavy boozing, came out of the lavatory. He nodded and led me the few steps to the drawing-room. On top of the piano were the four volumes of The Music Lover’s Portfolio. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, in a simple piano reduction, was distributed throughout Volume One. He found the slow movement and pointed to the mock-martial secondary theme: ‘That’s the tune,’ he said, and, bowlered, he played it with a fag in his mouth. ‘All you have to do is copy it out. That, by the way,’ pointing with a nicotined index, ‘is middle C. Under the treble stave or over the bass stave, it’s still middle C. And here it is on the Joanna.’ He prodded and it sounded. And then, fresh fag glowing, he went off to the Alec. He had given me a music lesson of exemplary brevity, the only one he ever gave, the only one I needed.

Burgess played the piano throughout his childhood in Manchester, and the piano appears in his writing in this context most substantially in his novel The Pianoplayers (1986), which is a bawdy semi-autobiographical work that describes the career of Billy Henshaw – an itinerant pianoplayer based on Joseph Wilson – and his daughter Ellen Henshaw, the narrator, whose early life is very similar to that of Burgess’s own.

The action mainly takes place in the pubs and clubs of 1920s and 1930s Manchester and Blackpool and provides an affectionate if clear-eyed portrait of the time; the climax is a marathon piano performance of thirty days and nights, perhaps inspired by Burgess’s own experience later in life of playing a piano accompaniment to Fritz Lang’s silent film Metropolis, which in its uncut form is four hours long.

Burgess wrote music for the piano all his career. He sometimes conceived of the piano as an essentially Romantic instrument, writing in Pianoforte: A Social History of the Piano that ‘the piano concerto … exhibited magisterially the heroic implications of a single man fighting, and being reconciled with, an orchestra of a hundred.’ Elsewhere he describes the harpsichord as the Alexander Pope of music, while the piano is its Lord Byron: ‘in Byron the hero is a man who detests war but glorifies his own ego. He loves largely, suffers from perturbations of the soul, is essentially solitary and tries to commune with Alps and rivers. He is an animated grand piano.’

One of Burgess’s most extravagant compositions is his Concerto for Pianoforte and Orchestra in Eb, which demands enormous instrumental forces and virtuoso excesses from the soloist. The Preludes are some of Burgess’s earliest surviving substantial solo piano compositions and provide several of the main themes of the concerto, and taken together they are entirely characteristic of Burgess’s distinctive style, with strong emphasis on fourths and metrical ambiguity.

Burgess concludes his praise of the piano in Lives Of The Piano in characteristically expansive terms:

Ultimately the piano is a most ingenious structure in which, under the hands of Rubenstein, or the single hand of a Wittgenstein, opposites are reconciled and acts of magic performed. The note begins to decay at the very moment of striking, but the illusion of durability holds. The instrument is a tuned drum, but it is also a human voice. Other stretched strings or vibrating air columns are competent to express a single aspect of the universe and the human life that tries to feel at home in it, but only the piano can attempt, in however miniaturised a form, the total picture. That is why it continues to deserve our homage and our wonder.