The Music of Anthony Burgess: Sonata for Violoncello and Piano

Explore one of Anthony Burgess’s earliest pieces, Sonata for Violoncello and Piano in G minor below.

Listen to the Sonata for Violoncello and Piano in G minor by Anthony Burgess, in the world premiere performance by Psappha in 2014.

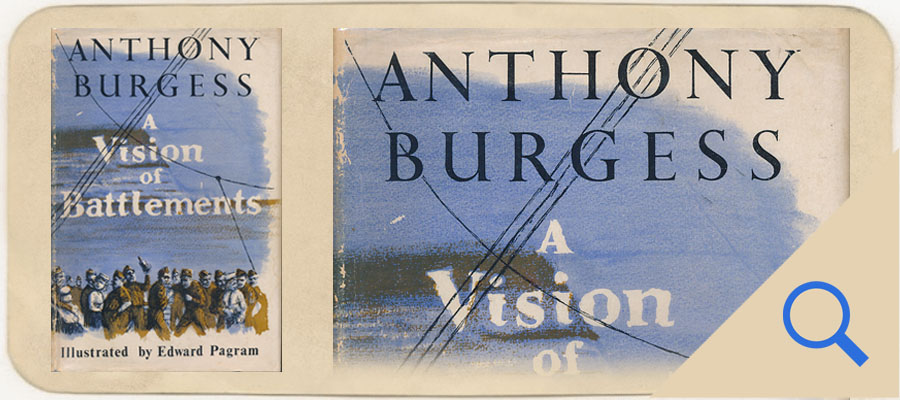

The first edition of Vision of Battlements, Burgess’s novel inspired by his wartime service in Gibraltar where the sonata was written.

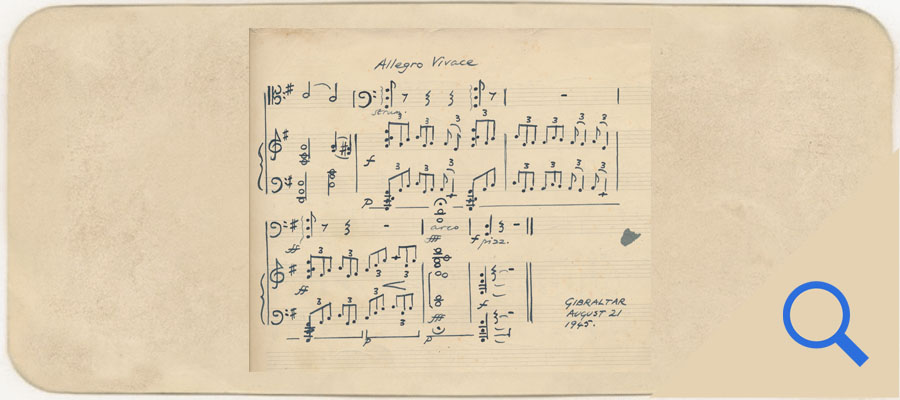

The final page of Burgess’s manuscript score of the sonata.

Anthony Burgess writing about his regard for the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins in 1989.

Sonata for Violoncello and Piano in context

This sonata is dated 1945 and was written during Burgess’s time in the Royal Army Education Corps.

While training in England in the early part of the war, he acted as musical director of a six-piece dance band, arranging popular songs and jazz standards and amusing himself by ‘fulfilling my boyhood ambition of wanting to have written L’Apres-midi d’un Faune by adapting it for the group, but the rhythms of jazz took over and sweating privates and their doxies danced to it.’

Later, Burgess was posted to Gibraltar, which provided a fertile ground for his musical activities.

‘One hundred quires of thirty-stave manuscript paper were found gathering dust in a quartermaster’s store,’ he records. ‘These had to be filled with dots.’

Burgess provided arrangements for a large dance band as well as composing marches for the military band, and otherwise spent his time organising musical appreciation societies, presenting gramophone concerts, and writing various pieces including a symphony in A minor, a cello concerto, an orchestral overture called Gibraltar and a choral setting of Wilfred Owen’s poem ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth’. Whether or not these pieces were in fact completed is unclear, as the sonata is the only work to have survived from this period.

Gibraltar was also an inspiration for writing projects. Burgess’s first completed novel was A Vision of Battlements, the first sketches for which survive in a notebook from his posting there. The protagonist, Sergeant Richard Ennis, is a lapsed Catholic composer, trying to find his place as the war comes to a close: sailing to Gibraltar, he dreams of composing a sonata for cello and piano.

Ennis lay in his hammock on the sergeants’ troopdeck, shaping in his mind, behind his closed eyes, against the creaks and groans of the heaving ship, a sonata for violincello and piano. He listened to the sinuous tune of the first movement with its percussive accompaniment, every note clear. It was strange to think that this, which had never been heard except in his imagination, never even been committed to paper, should be more real than the pounding sea, than the war which might now suddenly come to particular life in a U-boat attack, more real than himself, than his wife. It was a pattern that time could not touch, it was stronger than love.

The sonata itself is a substantial piece which provides an important key to Burgess’s musical career. The ambition of this piece, with its distinctively pungent tonality, angular melodies and quartal sonorities are entirely characteristic of Burgess’s mature work, stylistically similar to his Symphony in C and Piano Concerto, and some of the main themes are repeated in his Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, written nearly forty years later but never performed. The sonata indicates the level of seriousness that Burgess brought to his music at the earliest stage of his artistic career, and which did not leave him.

The second movement is marked ‘For the Dead: 1939-45’, and the work is prefaced by a poem by Gerard Manley Hopkins:

The shepherd’s brow, fronting forked lightning, owns

The horror and the havoc and the glory

Of it. Angels fall, they are towers, from heaven — a story

Of just, majestical, and giant groans.

But man — we, scaffold of score brittle bones;

Who breathe, from groundlong babyhood to hoary

Age gasp; whose breath is our memento mori —

What bass is our viol for tragic tones?

He! Hand to mouth he lives, and voids with shame;

And, blazoned in however bold the name,

Man Jack the man is, just; his mate a hussy.

And I that die these deaths, that feed this flame,

That in smooth spoons spy life’s masque mirrored: tame

My tempests there, my fire and fever fussy.