The Music of Anthony Burgess: Symphony in C

Explore Anthony Burgess’s Symphony in C below.

Symphony in C (first movement) by Anthony Burgess, performed by the Brown University Symphony Orchestra in 1997 and conducted by Paul Phillips.

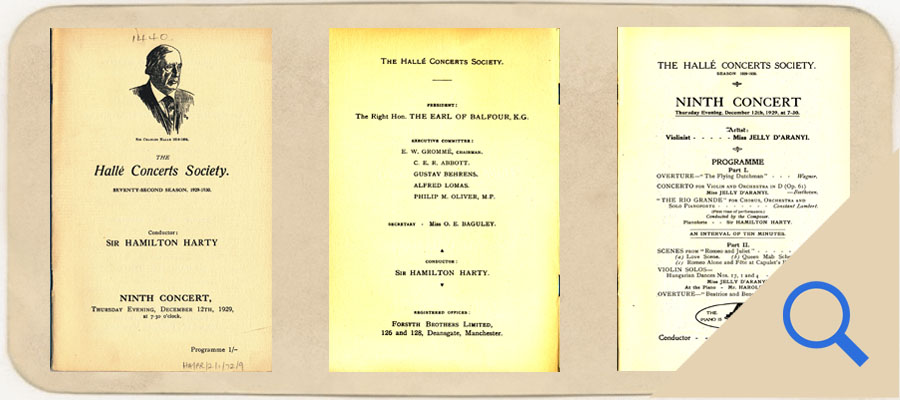

The programme for the concert given by the Halle Orchestra in Manchester on 12 December 1929 (first 12 pages of our scanned file featured here). With music by Wagner, Beethoven, Berlioz and Brahms, the centrepiece was the premiere of Constant Lambert’s The Rio Grande. Anthony Burgess attended this concert at the age of twelve with his father, and these experiences of orchestral music were formative in his development as a composer.

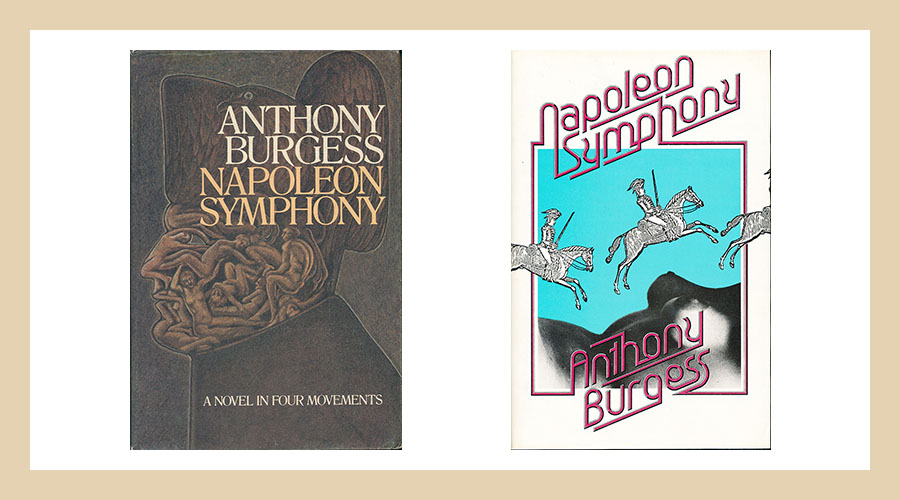

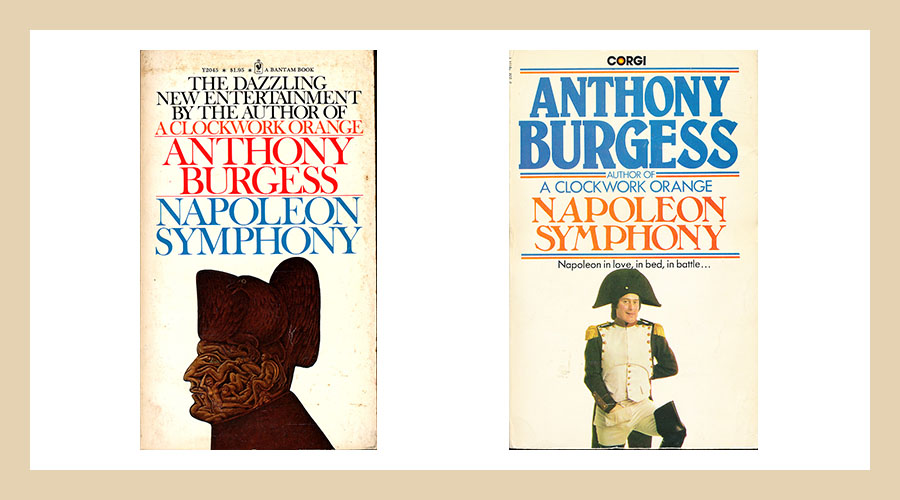

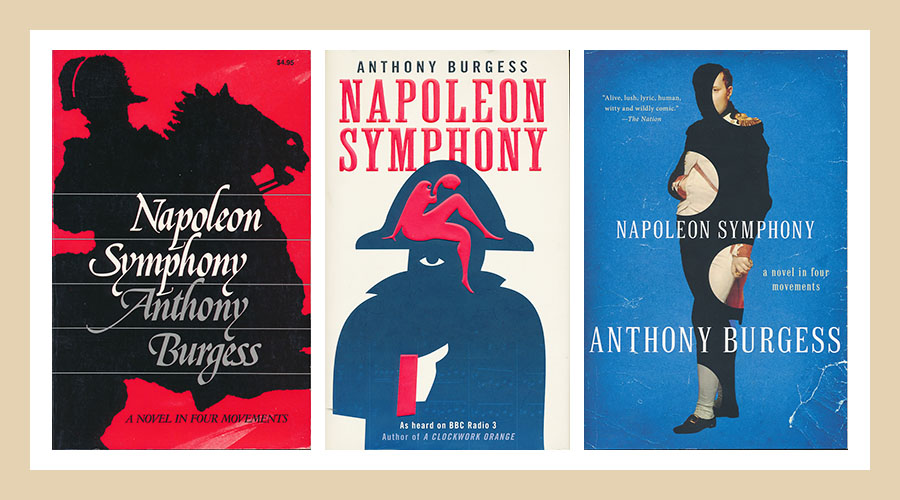

Anthony Burgess’s 1974 novel Napoleon Symphony, a rich, exciting, bawdy and funny novel that tells the story of Napoleon Bonaparte using the formal structure of Beethoven’s Third Symphony

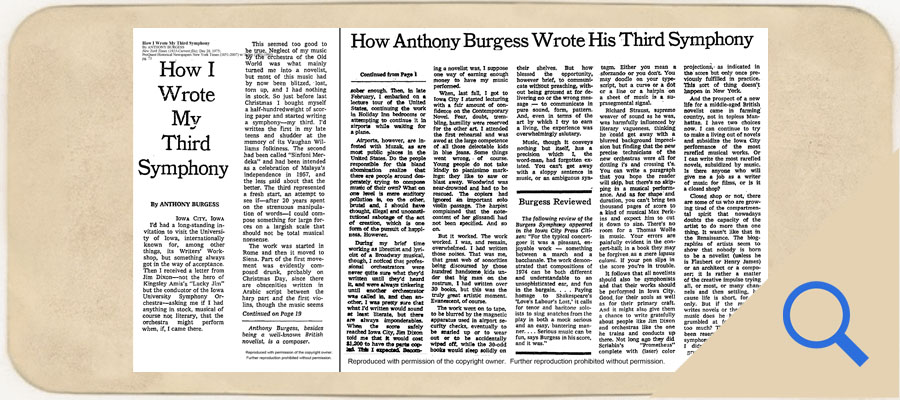

Burgess tells the story of how his symphony came into being in the New York Times — a review of the performance appears at the end of the article.

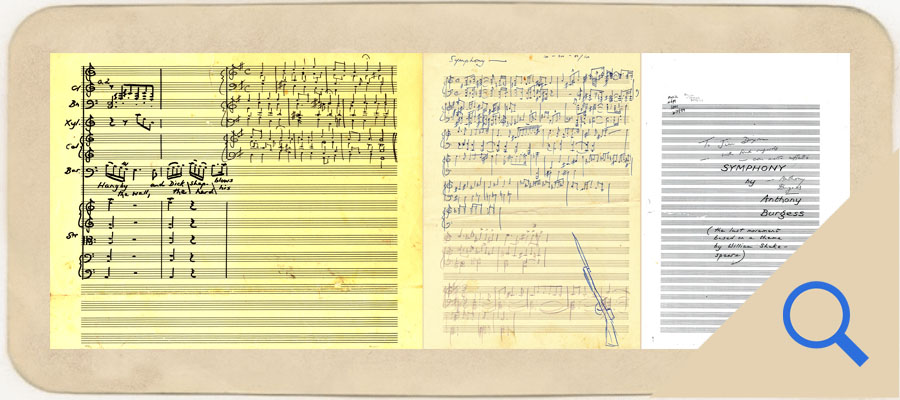

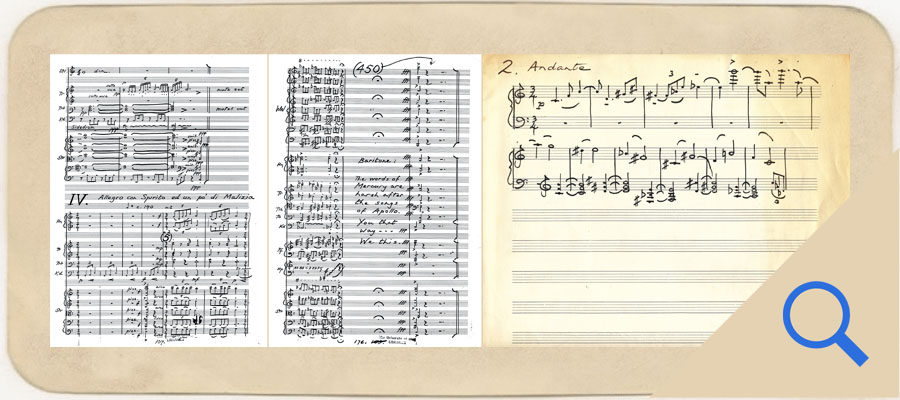

Pages from the manuscript score of Anthony Burgess’s symphony.

Anthony Burgess interviewed in Iowa City, the location of the first performance of his Symphony in C.

Symphony in C in context

Anthony Burgess was fond of describing himself as a composer who wrote novels on the side.

It is true that music was central to Burgess’s creative life from his early beginnings, from receiving basic instruction in the piano and violin as a boy, attending concerts given by the Halle Orchestra in the 1920s with his cinema pianist father, through to working as an arranger for a dance band in the Army Entertainment Corps during the war. Yet while Burgess never stopped composing music, in the first part of his career his activities as a novelist kept him at the typewriter rather than writing scores.

Everything changed in 1975, when James Dixon, conductor of the University of Iowa Symphony Orchestra, asked Burgess to write Symphony in C. Dixon had read Burgess’s 1974 novel Napoleon Symphony, structured around Beethoven’s ‘Eroica’ symphony, and was intrigued by the verse epilogue which describes in personal terms Burgess’s dream of giving ‘symphonic shape to verbal narrative’. Dixon offered to perform an orchestral work by Burgess should one exist.

Burgess claimed to have written two full-scale symphonies for orchestra by this time. Symphony No. 1 was, by his account, destroyed by enemy bombs during the war, and only a piano reduction survives; the score of Symphony No. 2 was lost by Radio Malaya in 1957 having been sent to them by Burgess. He set about composing an entirely new piece.

The symphony is in four movements, and is thirty five minutes in length. Generally tonal and stylistically conservative for the time, it is full of colour, texture, energy and dynamism and is particularly influenced by the work of Sibelius and Shostakovich, to whom the third movement is dedicated.

The final movement ends with spoken lines from Shakespeare’s play Love’s Labours Lost: ‘the words of Mercury are harsh after the songs of Apollo’. In Burgess’s description of the conclusion, ‘the orchestra then plays a single fortissimo chord of C major and everyone goes off for a drink.’

Never having heard his orchestral music played before, Burgess recalled later: ‘I had written over thirty books, but this was the truly great artistic moment […] I wished my father had been present. It would have been a filial fulfilment of his own youthful dreams.’

The Symphony in C is Burgess’s most ambitious composition and represents a high point in his journey as a musician. Received favourably by the audience and reviewed positively in the New York Times, Burgess was inspired to compose with new enthusiasm. The confidence that his symphony engendered led him to write music prolifically for the rest of his life.